Oversized Visitors

A cruise ship leaves Venice, Italy (above). The cruise ship, which arrived in Venice for the first time in 17 months, signaled the return of tourists after the coronavirus pandemic but enraged those who decry the impact of the giant floating hotels on this world heritage site. Natural and heritage sites around the world are under threat from over-tourism. As crowds flock to see unique sights, they become inadvertent destroyers of the very thing they’ve come to enjoy. The port in Venice (as in most ports around the world) can’t provide enough electricity to keep the services and amenities running onboard the ships, so ship engines run 24/7 to produce electricity.

Ship fuel is 1,500 times more polluting than car fuel, and a 100,000-ton ship will displace 50 million liters of water (the quantity of 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools) when entering a small location such as Venice. The movement of these massive amounts of water erodes the hundreds and even thousands of years old foundations of the palaces and the streets of Venice. The heavy digging of the canals to allow big ships to enter the Venetian Lagoon increases the amount of water that enters and exits the lagoon during tides, which increases the intensity of high tides, and partially floods the city.

Where Will the Children Play?

Children play on a beach filled with plastic waste in Manila, Philippines. The Philippines has been ranked third on the list of the world’s top-five plastic polluters of our oceans, after China and Indonesia. Many organizations and businesses have found ways (big and small) to help end plastic pollution and change people’s attitudes and behavior about their consumption and the impact it has on the environment. Over a million people have reportedly signed petitions worldwide, demanding that corporations reduce their production of single-use plastics. Without established recycling facilities, rapidly developing countries create mountains of disposable packaging like food-wrapping, sachets, and shopping bags that end up on coastlines after being discarded.

Most of these countries lack the infrastructure to manage their waste effectively. Those who live on lower incomes usually rely on cheap products sold in single-use sachets, such as instant coffee, shampoo, and food seasoning. According to studies, there could be more plastic in the sea than fish by 2050, while actual plastic pieces might become a regular ingredient of our seafood — as fish consume bits of plastic that are coated in bacteria and algae, mimicking their natural food sources — that eventually lands on our dinner table.

Here’s Looking at You

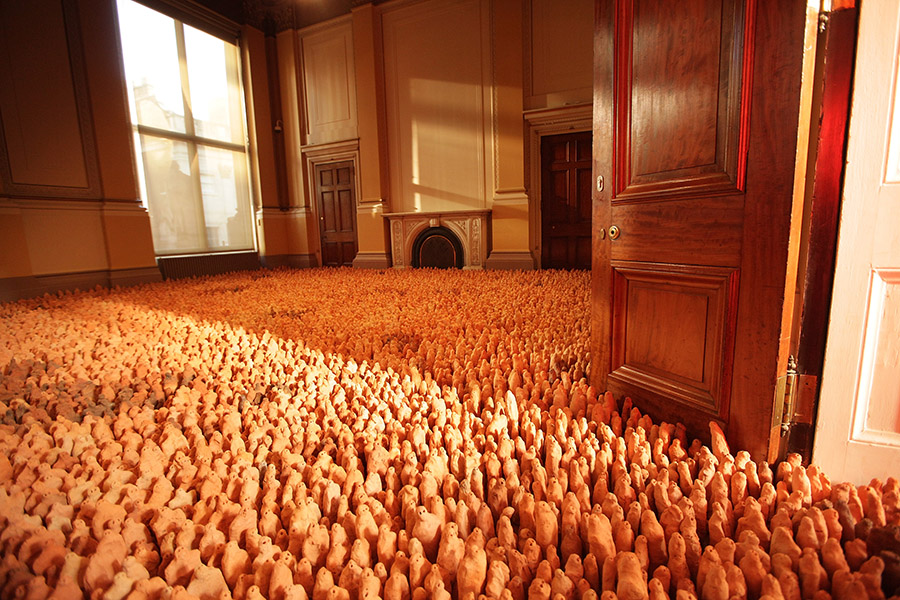

British artist Antony Gormley is well known for his life-size statues which mimic the human body. His Field series represents a different approach. Each work consists of tens of thousands of small clay figures, each of them between 8 and 26 cm high. They are all installed on the floor of a room facing the viewer. Gormley states that he wants to make works about our collective human future and our responsibility for it. His artwork aims to look back on its makers and the viewers as if they are all responsible for the world.

Gormley deliberately made this installation uncomfortable so that the viewer is cast as the main character who has subconsciously walked onto a stage and now faces an audience that seems to ask: Who are you? What are you? What kind of world are you making? The artist has recreated this art installation five times in different parts of the world, involving hundreds of locals to help make the clay figures. The involvement of these volunteers has added to the community awareness and collective sense of responsibility. “From the beginning, I was trying to make something as direct as possible with clay: the earth,” says Gormley. “I wanted to work with people and to make a work about our collective future and our responsibility for it. I wanted the art to look back at us, its makers (and later viewers), as if we were responsible for the world we are in.” What will you say to your audience when they ask “What kind of world are you making?”