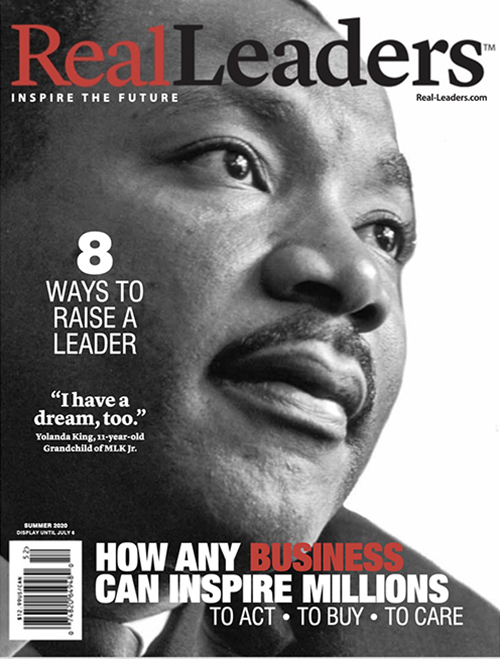

It’s been almost 52 years since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. As people once again take to the streets to highlight social injustice and atrocities across the country and the world, we ask: is his dream still relevant today?

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee (U.S.), almost 52 years ago, on April 4, 1968, an event that sent shock waves reverberating around the world. It was, as described at that year’s Nobel Ceremony in Oslo, a “bitter year for human rights” and “one of the most grievous losses ever suffered by the world’s champions of peace and goodwill.”

Dr. King, had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 for his nonviolent campaign for equal rights. The 1968 Nobel Peace Prize was presented to René Cassin for his work on drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948. Eleanor Roosevelt, who oversaw the writing of this milestone document had died a few years earlier and therefore could not share in the prize. The declaration presents 30 articles, each of which explains what rights we have as human beings regardless of “race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.” Importantly, Article 1 states that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”.

It was Dr. King’s dream that his children would one day “live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” That dream was rooted in his own experiences as a child growing up under “Jim Crow Laws”: a system of racial apartheid that dominated the American South for three quarters of a century, beginning in the 1890s. The laws affected almost every aspect of daily life, mandating segregation of schools, parks, libraries, drinking fountains, restrooms, buses, trains, and restaurants. “Whites Only” and “Colored” signs were constant reminders of the enforced racial order. Those who refused to abide by these laws were arrested, or worse, ‘lynched’ by white extremist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan.

Martin Luther King, Jr., was born Michael King,Jr. on January 29, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia (U.S.) and grew up in an area of the city reserved for people of color. His father, Michael King, Sr. (later Martin Luther King, Sr.) was a respected Baptist minister and community leader. His mother Alberta Williams King made it a point, early on in Martin’s life, to explain how young, healthy Africans were brought to the United States as slaves, and the ongoing realities of discrimination and segregation.

“You are as good as anyone,” his mother Alberta said, but Martin didn’t really understand until the day he went to school at age six. His best friend, a white boy that he had known and played with since age three, was told by his father to no longer play with him. “How could I love a race of people who hated me and who had been responsible for breaking me up with one of my best childhood friends?” Martin asked himself for a long time.

At fourteen years old Martin participated in, and won, an oratorical contest with an essay entitled The Negro and the Constitution in which he said, “If freedom is good for any it is good for all.” After receiving the prize, Martin took a bus home and unconsciously sat at the front, which was normally reserved for white people. The bus driver quickly reprimanded him. Martin recalls this incident as the angriest moment of his life!

At age 15 Martin entered Morehouse College, a historically all-male African American college established in 1867. It was during his time as a student at Morehouse that Martin would have his “first frank discussion on race” and where he would discover Henry David Thoreau’s essay on Civil Disobedience published in 1849, which tells the story of the author’s willingness to go to jail, rather than pay taxes to a government that supported slavery.

“I became convinced that non-cooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good,” said Dr. King.

Someone else who had an indelible impact on Dr. King’s beliefs and actions was the Indian activist Mahatma Gandhi, who, using nonviolent civil disobedience led India to independence from British rule in 1947. He was particularly moved by Gandhi’s 240 mile march from his ashram (religious retreat) to the coastal town of Dandi on the Arabian Sea. There, Gandhi and his supporters made salt from seawater, thereby breaking the British law that had established a monopoly on salt manufacturing.

“There is no way to peace, peace is the only way,” said Mohandas K. Gandhi (1869-1948).

Dr. King would put Gandhi’s technique of non-violence to good use in America’s own civil rights struggle. Starting in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama he successfully led a massive bus boycott after civil rights activist Rosa Parks had refused to give up her bus seat reserved for whites. Later on in Birmingham, a place he described as “where human rights had been trampled on for so long and fear and oppression were as thick in its atmosphere as the smog from its factories,” Dr. King was arrested and put into solitary confinement for leading a protest. From his cell he wrote a letter outlining that: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

While many nations in Africa, including Ghana (1957), had achieved independence from their former European colonial masters, the time had come for African Americans to be given full and equal rights – not only to sit at the front of a bus and attend integrated schools – but also the right to voice their opinions politically.

“Something within has reminded the Negro of his birthright of freedom, and something without has reminded him that it can be gained. Consciously or unconsciously, he has been caught up by the Zeitgeist, and his black brothers of Africa and his brown and yellow brother of Asia, South America and the Caribbean. The United States Negro is moving with a sense of urgency toward the promised land of racial justice,” he said.

And so the moment had come; a century after the abolition of slavery, marches were organized throughout the South, in Selma and Mississippi, and notably to Washington D.C., whereupon hundreds of thousands of men and women, black and white, rich and poor, marched on the United States capital demanding economic justice. Youth from all over America traveled South to join the ranks as Freedom Riders and to participate in more provoked, but still nonviolent, actions of civil disobedience.

Thanks to mass mobilization, enough pressure was brought on the United States government to bring about significant changes to federal law, notably the 1964 Civil Rights Act that ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. The 1965 Voting Rights Act was described as, “one of the most monumental laws in the history of American freedom”.

It was at this time, that Dr. King would travel to Oslo, Norway, to receive the Nobel Peace Prize on December 10, 1964. During his Nobel lecture on December 11, he said:

“The Nobel Prize is the second greatest honor given to me in my lifetime. The honor of the first importance was the response of the millions of Negroes to the doctrine of nonviolence, and their heroic employment of it to achieve equality and freedom. In a sense they earned the Nobel Prize when they stood against guns, dynamite, snarling dogs and prison without flinching, until their steadfastness muzzled the weapons of their oppressors.”

Following the Nobel Prize, Dr. King turned his attention to fighting other injustices: poverty and war. At the time, the United States was, in his opinion, wasting enormous economic resources fighting a war in Vietnam that he felt would be better spent on helping the poor.

“If we assume that life is worth living and man has a right to survive, then we must find an alternative to war,” he said. Dr. King was 39 years old at the time of his death, which occurred as he was planning a massive ‘Poor People’s Campaign,’ involving the wider participation of American Indians, Mexican Americans and other racial and ethnic minority groups.

Given the present global challenges to Human Rights, Dr. King’s message of nonviolent social and economic justice is as important today as ever before.