- Alfred Nobel spent a lifetime developing armaments only to have a change of heart on their effectiveness a few years before his death.

- He leaves his vast fortune to establish a prize for those who achieve excellence in various fields, including peace.

- A big thinker, and ahead of his time, Nobel insists the prize be given to anyone who qualifies, regardless of their nationality.

- His social and peace-related views are seen as radical in his day, something we regard today as a desirable thing when creating new and innovative businesses.

- Nobel’s ideas on leaving a positive legacy have been emulated by people such as Warren Buffett and Bill Gates.

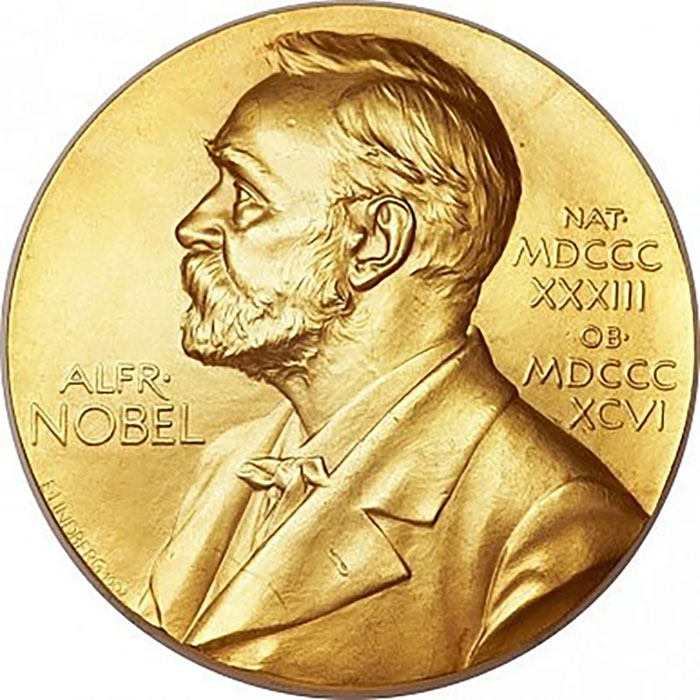

In December 1896, a group of people gathered in Paris to hear the reading of Alfred Nobel’s will, a renowned engineer, innovator and inventor. Best known as the inventor of dynamite, Nobel had amassed a fortune of nearly £2 million, around $500 million in today’s terms. After the reading of his will there was an uproar, Nobel had left 94 percent of his assets to the establishment of a prize.

His shocked family opposed the establishment of the Nobel Prize and the first prize awarders he named in the will refused to comply with his wishes. It took five years before the first Nobel Prize was awarded in 1901. It was a scandalous start, at the time, to what has now become one of the world’s most prestigious and recognized awards.

How does the inventor of dynamite end up being associated with peace, you may ask? The Nobel family had a history of weapons manufacturing, beginning with the family factory producing armaments for the 1853-56 Crimean War. When the war ended, they had difficulty returning to domestic production and they filed for bankruptcy. Nobel continued the family tradition by devoting himself to the study of explosives; especially the safe use and manufacture of nitroglycerine and with his skills eventually developed his most famous invention – dynamite. He patented it in the U.S. and U.K. and it soon became a staple of mining and transport-building sectors around the world.

During his lifetime Nobel issued 350 patents internationally and by his death had established 90 armaments factories, despite his belief in pacifism. His promotion of peace began one day when he opened a newspaper and was shocked to read a headline about his brother’s death. It read: “ The merchant of death is dead.” Many had mistakenly thought it was Nobel himself who had died.

Horrified that this was how he might be remembered one day, he began formulating a way of reversing this image. He decided to use his estate to endow, “prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind.” Being a businessman and entrepreneur, Nobel knew that nothing motivates more than money, prestige and accolades.

It’s a strategy still used today to encourage excellence and social good. Think of the XPRIZE, founded by Peter Diamandis, that offers millions of dollars to those who can solve problems for the benefit of humanity, or The Giving Pledge, started by Warren Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates, that invites the world’s wealthiest individuals to commit more than half their wealth towards addressing society’s most pressing problems.

Nobel established five categories for his prize – physics, chemistry, medicine, literature and peace. In his will he worded a vision for how the peace prize should be awarded: “to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.”

In true visionary style, and in a time when diversity was more associated with zoology than culture or gender issues, Nobel added a final phrase to his last wishes: “It is my express wish that in awarding the prizes no consideration be given to the nationality of the candidates, but that the most worthy shall receive the prize.”

For those big thinkers who like the idea of having their wealth change lives for the better, a century after their death, there is a word of caution – interpretation is everything. Sometimes a great idea, expressed too broadly, can be misread by those you have been tasked to action it. In Nobel’s case, his formulation for the literary prize was a work “in an ideal direction” and he never properly distinguished between science and technology, leaving the door open for skewed nominations in the future. Trying to keep your original purpose clear without knowing what the world will look like in 100 years time, or even if your chosen field of interest will still exist, can be a challenge.

Nobel was interested in social and peace-related issues and held views that were considered radical during his time. It’s become evident throughout history that many ideas we now consider perfectly normal were once seen as outrageous or crazy when first made public. In fact, many would argue that if your idea is not labeled crazy, it’s not even worth pursuing.

To Nobel, having a wide interest in global affairs was important to his formulation of the peace prize. Many of his inventions and business activities were connected with the conditions of war and peace. A significant influence on his attitude towards peace came form Austrian countess Bertha von Suttner, with whom he maintained a 20-year correspondence. Von Suttner was a peace advocate and author of the famous anti-war novel Lay Down Your Arms. Many believe she had a major influence in Nobel’s decision to include a peace prize among the other prizes in his will.

Von Suttner was actively involved in the international peace movement, which formed in Europe at the end of the 18th century and tried to get Nobel more actively involved. He wrote to her: “Good wishes alone will not ensure peace,” and suggested a more pragmatic approach. Commenting on his dynamite factories he told her: “Perhaps my factories will put an end to war sooner than your congresses: on the day that two army corps can mutually annihilate each other in a second, all civilized nations will surely recoil with horror and disband their troops.”

Nobel’s solution was to create a weapon so terrifying that war would become impossible. While you can argue the merits of using weapons as a deterrent, one thing is sure – Nobel realized at some point that weapons of destruction don’t bring about lasting peace – only people can. Seven years before his death at age 63, and unknown to anyone, he drew up a plan to promote peace that has inspired millions since and saved the lives of countless people through the Nobel Peace Laureates his prize has honored. Truly a big thinker, he has ensured that his legacy of peace has lasted 120 years beyond his lifetime – 57 years longer than he himself was alive.