Books on professional success often say that it is more important to strengthen your strengths rather than improve your weaknesses. On the one hand, they’re right; on the other, this doesn’t go far enough.

It sounds logical – and it is: You shouldn’t waste your time trying to be good at things you never stand a chance of being among the best at. It is far more efficient to focus on your strengths and become even better in these areas. If you heard me sing and I asked you to rate me on a scale of minus 10 to plus 10, you would probably give me a minus nine if you were charitable and a minus ten if you were honest. I believe that, with a lot of hard work and perseverance, I could improve by 10 points over the next few years. That is an enormous improvement. But where would that get me? Would that get me any form of recognition? Well, my friends, who knew that I started as a minus 10, would pat me on the back and congratulate me. But for everyone else, I’d still be a zero: no one would hire me as a singer; I wouldn’t be able to earn a single dollar with my singing, let alone win a prize. Would it be worth the effort?

Strengthening your strengths

This requires an alternative scenario: Let’s take an activity where I am good, e.g., a keynote speaker. The fact that I regularly receive invitations from all over the world to give lectures indicates that I am good in this field. Probably most people would give me an 8 or 9 on our scale of minus 10 to plus 10 – at least if they experienced me at my best, on a day when I am on top of my game. Professionals, however, i.e., the world’s best speakers, would probably be more critical and perhaps give me a five or a six. If I focused all of my time and energy on improving my skills as a speaker rather than working on my abilities as a singer, I might improve by 3, 4, or even 5 points – and I would be one of the best speakers on the circuit. People would want to hear me speak, and I could earn a lot of money giving talks.

So, the idea that we should focus on strengthening our strengths rather than working on our weaknesses has a lot going for it. Nevertheless, I would like to make an essential qualification. As Geoffrey Colvin demonstrates in his book Talent is Overrated, it is not talent but “deliberate practice” over years and decades with unrelenting self-discipline that is the main reason for people’s success. The length of time spent practicing, and the intensity and method of practice vary considerably between the best performers and average experts in their field.

The secret of elite performers

But it is not only the length of time and the intensity of the practice that counts, but also the type of practice. What many people understand by ‘practice’ has nothing to do with the “deliberate practice” of which Colvin speaks. Performing a particular activity in the same or similar way over and over again does not, of course, lead to the kind of dramatic improvements necessary to achieve excellence. Instead, a key feature of “deliberate practice” is that great performers concentrate on a very specific aspect of what they do and focus on that until they make significant progress. They identify very specific sub-areas that need improvement and approach them systematically. True masters of their trade focus their practice on those specific aspects and work on them, single-mindedly, relentlessly until no further improvement is possible.

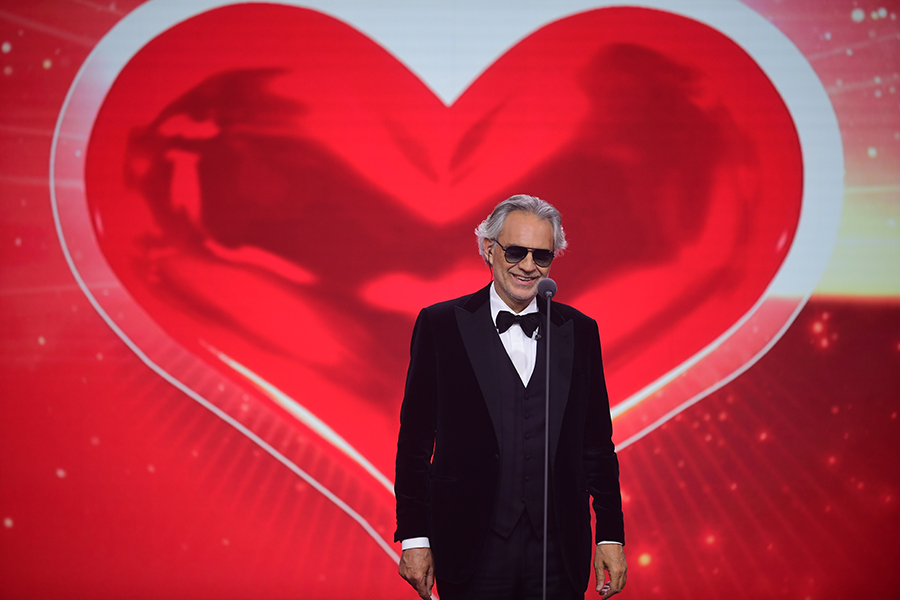

Learn from the superstar Andrea Bocelli

Once you have identified a particular strength, you may need to hone in on any residual weaknesses and work on them. This is precisely what Andrea Bocelli did. He is not only one of the most successful Italian singers of all time, but he is also one of the few who have established themselves on a global stage in both pop and classical music. He has performed in front of presidents of the United States and several popes and filled concert halls worldwide. His albums have reached the upper echelons of the charts, received multiple platinum awards, and won major music prizes such as the World Music Award, ECHO, Classic Brit Awards, a Bambi in the field of classical music, and a Billboard Award. He has also been nominated for several Grammys.

Although Bocelli, who was born with an eye disease and went completely blind at the age of 12, earned praise for his singing from those around him early in his life, he remained self-critical. For his friends and acquaintances, he was the greatest – and increasingly for other people too. In his autobiography, however, he writes that he subjected his songs to critical analysis and came to a conclusion, “that they did lack a certain originality and, probably, even strength.”

A piano tuner told the singer to take singing lessons

One day a piano tuner said to him: “Forgive my frankness, but I feel it is my duty to tell you that, with your voice, you could go a long way if only you entrusted yourself to a good singing teacher.” Bocelli was amazed. For years, no one had spoken to him about studying singing. The piano tuner recommended an exceptional teacher, Luciano Bettarini, who had trained numerous opera singers, including Franco Corelli. Other singers might have been offended to have a piano tuner recommend that they take singing lessons. Bocelli, however, listened to the advice he was given and contacted Bettarini.

After Bettarini had heard him sing, he said: “You have a voice of gold, my son!” before adding, “But you do the exact opposite of what you should do when singing. Proper study would not only improve your interpretative qualities, but it would strengthen your voice; in short, it would put you in a new league. What I mean, to be frank, is that to the ear of the uninitiated, you may sound surprising, but to the ear of an expert, the defects of your voice are egregious.” Nobody had ever spoken to Bocelli this way before, but he was eager to learn and from that day on took lessons with the maestro. Thus, Bocelli did the two things that matter: He focused on his strength – singing – and dedicated himself to systematically improving the weaknesses of his voice.

I try to learn from Bocelli’s example. I often give lectures in Asia and the United States – in English. I have no natural talent for foreign languages. Even at school, I was better at maths, physics, and chemistry and awful at French. So, I had to work on my English. For a few months now, I’ve been taking a – very expensive – course three times a week with a leading coach to help me improve my pronunciation in English and reduce my German accent. So, within a field of strength, I am working on my weaknesses. And after my last lecture in China, I gave the recording to one of the best rhetoric trainers in Germany. I asked him to critically analyze the weaknesses in my delivery.

So, yes, strengthening your strengths is a good idea. But if you don’t self-critically and persistently focus on your weaknesses within your area of strength, you will never be one of the best.