- A family decides to invest in a rainforest in Ecuador, believing they can preserve it for future generations.

- Rather than hide it away, a sustainable business model is drawn up that sees it become a highly visible a tourist lodge.

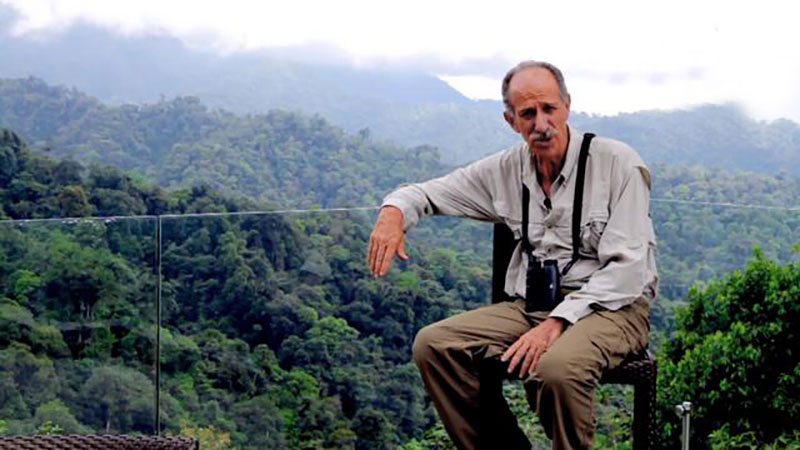

- Miguel Sevilla believes that rarity is a powerful marketing tool and that different conservation practices should apply to large and small destinations.

- Conservation is a problem we should all take seriously, regardless of where we live. After all, we all breathe the same air.

Most people who seek investment opportunities with decent returns will put their money into real estate, jewellery, art, shares, bonds or a promising Silicon Valley startup. Miguel Sevilla’s family decided instead to buy a patch of rainforest in Northwest Ecuador. The land is untouched, a pristine piece of earth made up of primary jungle, or virgin forest, as we like to call it in the West. Secondary jungle, that has seen human intervention exists alongside, and while still beautiful, is less rare.

Clearing the land for cattle ranching, farming or logging might deliver fast, short-term profits, but the Sevilla’s think it’s a much better investment left untouched. They also decided to create a unique hotel to give people from around the world an opportunity to appreciate its beauty and better understand why rainforests are important.

Every hour, 6,000 acres of rainforest are cut down. That’s the equivalent of 4,000 football fields. Trees are not just nice to look at; they form an important part of our ecosystem and are crucial in sucking carbon monoxide from the air. When we exhale, trees inhale. Besides keeping the air clear, the rainforests of the world cover eight percent of the world’s land surface and are home to more than half the earth’s animals and plant species.

After securing their investment in nature, the Sevilla family began to formulate a sustainability plan. “Our first idea was to preserve it for the sake of preservation,” recalls Sevilla. “It turned out to be a weak defence against the threats it faced from future logging or poaching, so we decided to make it more visible, instead of hiding it or protecting it like a trophy in a museum.”

Creating a legal and commercial entity for their investment helped with their concern that future owners or generations might be tempted to do something else with the land. Turning the lodge into a successful business venture was insurance against this.

The idea of Mashpi Lodge was to keep the rainforest in the public eye in the hope that visitors would spread the message of conservation. The first challenge was how to build a structure of concrete, glass and metal in an area that was going to market itself as “untouched.” Luckily, in an area of secondary jungle that formed part of the purchase, a Spanish logging company had cleared a small patch of jungle decades earlier for its operations. It was the perfect location for the lodge and a short walk from the unspoilt forest that was to become the main drawcard for guests. Ironically, the Spanish logging company had gone bankrupt because of the diversity of trees in the area; they couldn’t find enough of the same to type to make their business viable. When people speak of nature fighting back, this might be one good example.

“To avoid clearing a path from a road seven miles away to install electricity poles, we created our own, small hydro electric plant on the premises,” says Sevilla. “To take sustainability seriously, you sometimes need to consider solutions that are not necessarily profitable at first. You also need to acknowledge issues that are larger than the people involved,” he muses.

Guests to Mashpi Lodge sleep in rooms with glass walls, surrounded by jungle, giving an impression they are living in nature, and maximizing the full beauty of their surroundings. Arial bicycles, suspended on steel cables, transport guests through virgin forests, ensuring that even footprints are not left behind.

Keeping the lodge and its surrounding rare is a marketing strategy that Sevilla embraces wholeheartedly. “Mass tourism, like you see in Ecuador’s capital Quito, has a different type of effect on the environment and needs different conservation methods,” he says. “Large and small destinations alike should introduce unique eco-friendly measures that take advantage of their size. The Galapagos Islands, for example, have quotas that restrict the number of tourists per year due to environmental sensitivities.”

Sevilla believes the rarity of their investment at Mashpi will help ensure they are fully booked throughout the year, rather than seasonal highs and lows. Restricting customers might seem unintuitive to running a healthy business, but in Sevilla’s case it works.

The social pressure for short-term benefits at the expense of the environment, especially in poverty-stricken nations, is very strong. It’s usually ignored by many people in the developed world and viewed as being someone else’s problem. However, this is a global issue that affects rich and poor, a collective problem we all should help resolve.

“Rainforests being destroyed in Ecuador will effect the oxygen levels in Germany – we all breath the same air,” says Sevilla. He feels that rationalizing the concept of time to people is important in understanding conservation. “When you try and explain to guests that a tree is 1,000 years old, it’s unbelievable to most. Putting facts such as these into a rational perspective, that people can understand in their everyday life is crucial for conservation,” he says.

Mashpi Lodge doesn’t only welcome tourist wanting to experience the rainforest first-hand. American universities have used the lodge to study birds and an important research program is underway to reintroduce an almost-extinct spider monkey back into the region. One of the guides is a former poacher, who now has the means to earn a living through legal means. “Our staff, who are drawn from local communities, are excellent examples of how changing someone’s circumstances can make them great ambassadors for sustainability,” he says.

“As a human being it’s impossible not effect our planet environmentally,” says Sevilla. “Even our breath leaves a footprint. What we need to learn is how to manage this footprint better.”

Mashpi Lodge is a recent winner of an IE Award for Sustainability (Premium and Luxury Sectors) www.ie.edu/ie–luxury–awards