Doctors without Borders (Medicines Sans Frontiers – MSF) is not the first organisation to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, there have been 20 organizations, foundations and institutes that have been awarded the prize since its inception in 1901. Many individuals who have won have become laureates because of a single act or from becoming known as a champion for peace against a particular struggle, an organization because of it’s global reach.

Medicines Sans Frontiers was founded in 1968 and selected for the prize in recognition of its pioneering humanitarian work on several continents. Their work is now spread over 80 countries and they have treated tens of millions of people. They provide assistance to populations in distress, to victims of natural or man-made disasters, and to victims of armed conflict, and they do so irrespective of race, religion, creed, or political convictions.

James Orbinski (pictured above) was the president of Doctors Without Borders when the organization was awarded the prestigious Nobel Peace prize in 1999 and his opinion is that consistency and a strong commitment from staff is the reason they won. They are also known for more than just their medical work – they also speak out on behalf of the people they treat and act to expose injustice.

Using his acceptance speech at the award ceremony, as a platform to speak out, Orbinski spoke directly to the then Russian leader Boris Yeltsin and condemned that country’s violence against civilians in Chechnya.

Justifying this unprecedented move, Orbinski said: “Silence has long been confused with neutrality, and has been presented as a necessary condition for humanitarian action. From its beginning, MSF was created in opposition to this assumption. We are not sure that words can always save lives, but we know that silence can certainly kill.”

A strange trait of humanity is that governments always seem to find money for weapons and war but not for medical supplies. “An act of charity is not a necessity for many governments,” says Orbinski. He’s the first acknowledge both the power and the limitations of humanitarianism.

“No doctor can stop a genocide. No humanitarian can stop ethnic cleansing, just as no humanitarian can make war. And no humanitarian can make peace. These are political responsibilities, not humanitarian imperatives. The humanitarian act is the most apolitical of all acts, but if its actions and its morality are taken seriously, it has the most profound of political implications. And the fight against impunity is one of these implications,” he says.

Orbinski’s defining moment came about while working in Somalia in 1992 during the famine and civil war. He developed pneumonia and then meningitis and I was flown out to Nairobi, Kenya for treatment. At the time, he was also struggling to find doctors to work in Somalia, a country where they were trying to treat 100,000 patients. “I remember looking at myself in the mirror of the hospital washroom,” he says. “ I realized that if I didn’t go back, I could never look at myself the same way again, I would have failed. The question to myself was was, ‘Will you go back?’ My answer was ‘Yes!’”

Orbinski witnessed atrocities so horrific that he struggled to continue at times. Yet, he knew the people they were helping needed the assistance more than his personal coping problems. “There are moments when you can become overwhelmed,” he says. But you need to recognize that if you have the capacity or ability to respond to another’s circumstances, then you should.”

He’s a strong believer in looking beyond the “Band-Aid” – approach of patching something up and moving on, but acknowledges that the Band-Aid approach has its merits.

“You do it so that a person or community has an unbearable and intolerable suffering relieved,” says Orbinski. “It can be the first step in helping people restore their own economy or political system. It’s worth it because it allows a person who’s suffering to become an active participant in determining their own destiny.”

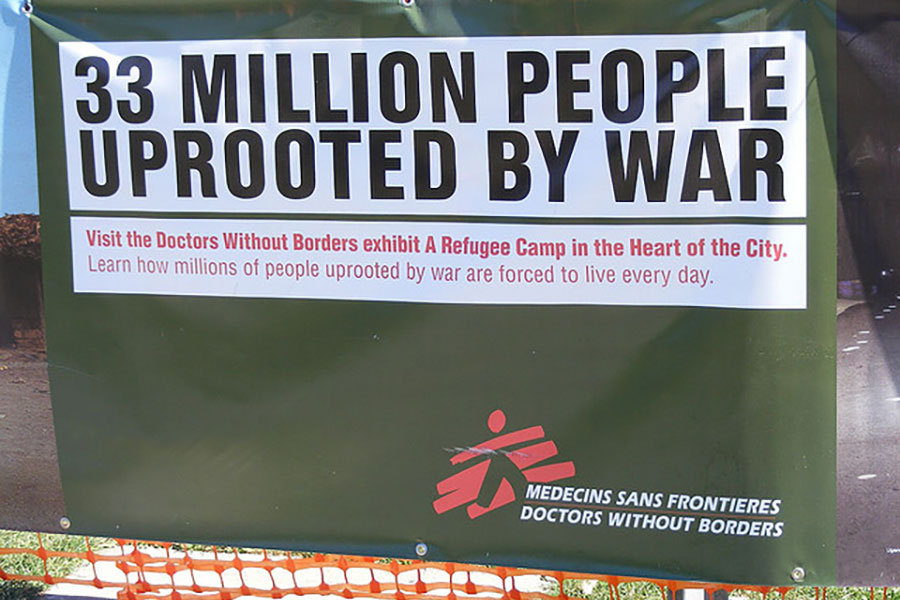

The latest global crisis is the hundreds of thousands of people fleeing the war Syria and Iraq. Thousands are dying in a desperate attempt to enter Europe with their families. Orbinski is clear on how we should view these people. “It’s not an immigration crisis. These are not immigrants –they are refugees,” he says.

“To risk the lives of you and your family, you have to be leaving a situation that is far worse than the risk you are taking.”

He also wants to dispel the myth that these are people simply looking for jobs, for the so-called “better life.” Many like to refer to.

“It’s not the choice of a nation to refuse a refugee, says Orbinski. “This has been international law since the Second World War. I remember very well the slogan that emerged after this war; around the Holocaust and the massive numbers of people moving across Europe and the world – never again.”