Here’s a bit of a thought experiment. Austria has an organ donation rate of 90 percent, meaning 90 percent of its citizens donate their organs at time of death, while Germany sees less than 15 percent.

Here’s a bit of a thought experiment. Austria has an organ donation rate of 90 percent, meaning 90 percent of its citizens donate their organs at time of death, while Germany sees less than 15 percent.

Why such a large disparity among neighboring countries? A 2012 study from Stanford University has the answer—the former makes organ donation the default option, while citizens of the latter must “opt-in.”

The findings can be applied to any number of policies to help guide positive social outcomes, and one in particular comes to mind; environmental, social and governance investing (ESG).

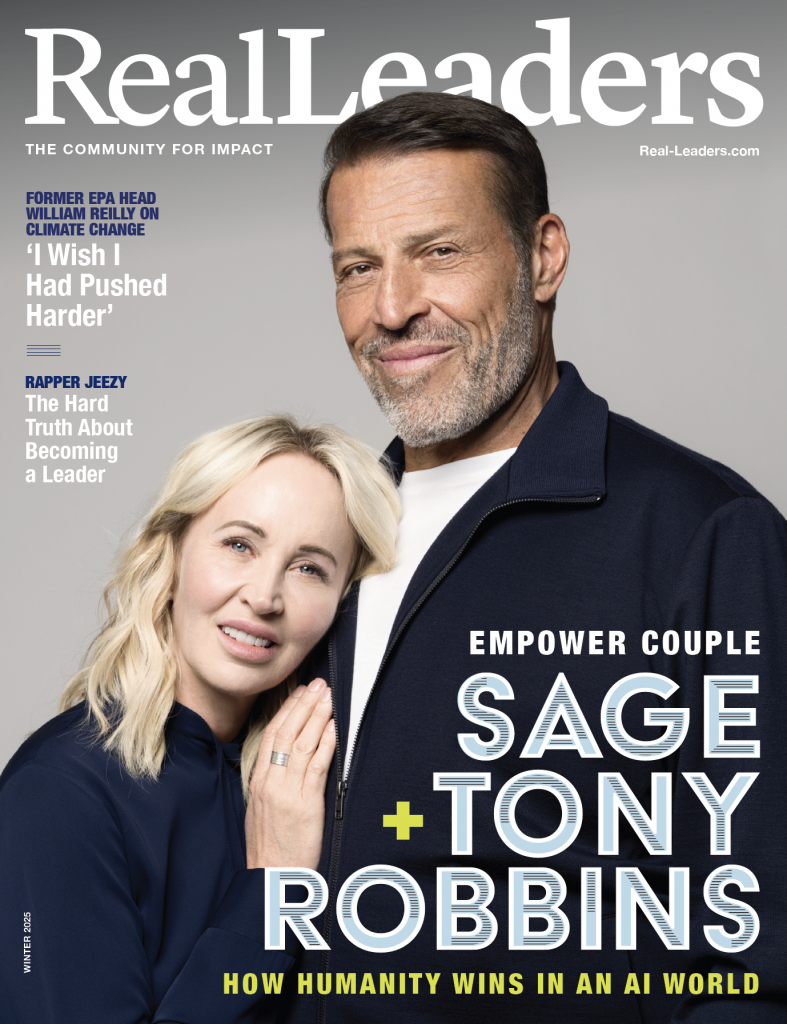

“If we can take that same model and apply it to ESG investing, what would it look like in the capital markets?” Matthew Weatherley-White (pictured above) rhetorically asks. “How could that potentially change our perception of the challenges embedded in ESG investing?”

Weatherley-White is managing director of The CAPROCK Group, a firm that provides family-office wealth management and outsourced chief investment officer services. He says issues like natural resource efficiency, climate risk and the potential cost of carbon are on everyone’s mind, yet the amount of capital currently allocated to ESG and impact investing is relatively small.

An opt-out model would make the process easier and “a lot less threatening.” And even though direct ESG market penetration is small, many assets mangers might not self-identify as impact investors even though they incorporate its precepts, something Weatherley-White refers to as “ESG creep.”

Which is important, because ESG and impact investing can unleash capital markets for positive impact, he argues, calling it “the most powerful optimization vehicle on the planet.”

Corralling Capitalism

When attempting to “corral such a force” to realize the benefits of impact investing, Weatherly-White points to three critical areas:

- Models of effectiveness: ESG asset managers have strong investment performance. When enough “gravitational pull” occurs around a successful impact strategy, it shifts the capital market’s perspective about the strategy.

- Regulation: Rather than laws to enforce the application of impact or ESG, regulation means internalizing cost structures that traditionally have been externalized. “An example might be coal,” says Weatherly-White. “We know burning coal leads to increased health costs in communities immediately downwind—and increased environmental costs. Those are known costs, and they’re borne by taxpayers, so they are externalized to the cost of the commodity. Internalizing those costs” can change investment prospects.

- Paradigm shift: More Austria and less Germany, meaning the aforementioned opt-out model as the new standard. When combined with more education to combat the widespread (and incorrect) notion that investors must sacrifice return to realize a positive social or environmental impact, these changes will significantly increase ESG adoption. “While one might intentionally accept concessionary returns in order to build a new market, or test a pre-scale service delivery model, one does not need to sacrifice performance in pursuit of impact,” he explains.

Incremental and Total Impact

As a longtime champion of ESG and impact investing, Weatherly-White also recognizes that impact investing is not absolute. Initially, a percentage of assets can be allocated that corresponds with investor comfort. This often leads to interesting revelations, and the behavioral choices that naturally follow.

“At some point, investors realize they’re trying to solve problems with one part of the portfolio that the rest of their portfolio is creating,” he notes. “What we’ve seen is that once investors start down the ESG path, they often continue in that direction, and move toward a complete allocation.”

While some investors are 100% impact investors from the start, performance drives others to increase their allocation. “Once they see returns generated in a responsible way, they ask themselves why they wouldn’t want to do more of it, and it becomes a really different conversation.”

Beyond investment return, investors want to know if they are truly making an impact. This second piece, benchmarking social and environmental impact, is more difficult to measure. Weatherley-White turned to tech for a solution, creating an impact reporting platform called Impact Portfolio Assessment and Reporting (iPAR).

“We require that our impact managers use it in tracking their Impact Reporting and Investment Standards (IRIS) metrics, which include the number of tons of carbon not generated, or solar power used, or whatever it might be.”

Just Do It

For successful entrepreneurs, executives and investors looking to enter the impact investing space, Weatherly-White says opportunities are growing rapidly in a variety of sectors.

“From a personal perspective, the best advice I would give is just get started,” he says. “There is no performance sacrifice required. Take a step, and there’s lots of places to get started. It’s not intimidating once you’ve taken the first step.”

For those looking to run their business in a sustainable manner, he suggests the B Lab Impact Assessment, an online tool to help business owners measure their organizations’ social and environmental impact.

“It gives a window into best practices in sustainable business management,” says Weatherly-White. “You don’t have to get all the questions right immediately, but pick a few things you can improve on over the next year and steadily work toward incorporating them.”