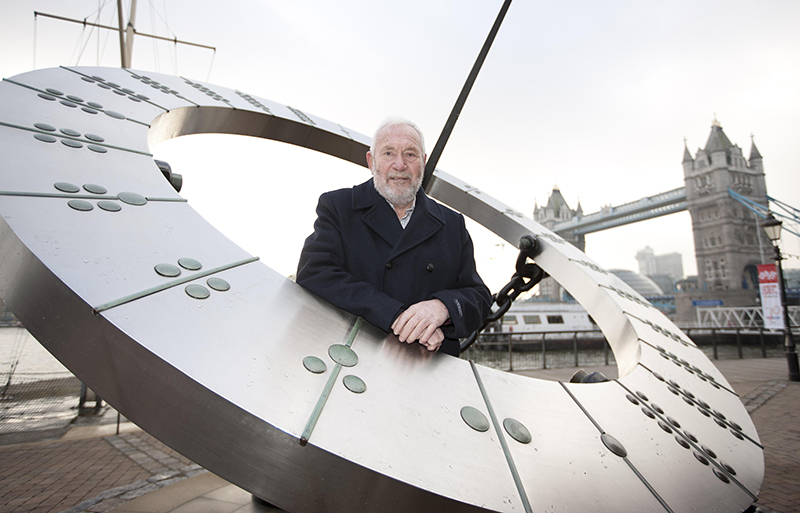

The first person to sail solo around the world has some valuable lessons for business, while teaching ordinary people about the ocean.

Somewhere in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, two months into a grueling attempt to circumnavigate the globe, and all alone, Robin Knox-Johnston felt like giving up. The year was 1968 and a London newspaper had thrown out a challenge to see who could be the first to sail single-handedly, non-stop around the world. The Sunday Times Golden Globe Race saw nine sailors leave Falmouth, England and only one return.

Now, many years later, and having been knighted by the Queen for his accomplishment, Sir Robin Knox-Johnston recalls what kept him going in his darkest hour. “I needed to rationalize things,” he says of that day. He told himself, “If I give up today, I’m letting down the me who worked bloody hard for the last two months to get here. I have no right to do that. Therefore I won’t.” With no crew, or physical contact with another human being for months, Knox-Johnston needed to keep himself motivated.

Of the nine competitors in the Golden Globe race, four gave up while still in the Atlantic, one gave up on the tip of Africa, one sank, one committed suicide and the only Frenchman in the race ended up rejecting the whole challenge as being against his philosophy on commercialization and headed for Tahiti. Forty six years later, he now gives advice to management consultants, CEOs, doctors, students and nurses, all wanting to overcoming their fear of the unknown in equally challenging conditions.

Clipper Ventures, which has the tagline, “Raced By People Like You,” have had every age between 18 and 72 on a race and more than 40 nationalities take part. Experience doesn’t matter at all. Knox-Johnston is looking for desire, determination and enthusiasm; a team player who is tolerant and supportive. With the promise of life-changing experiences, varied talent working as a team on cutting-edge personality building, you might even call each Clipper race the equivalent of a start-up at sea. The drive to share his passion for the ocean with as many people as possible started in Greenland while climbing a mountain with a friend.

The friend told Knox-Johnston how much it cost to climb Mount Everest; a feat he had recently accomplished. He recalls being surprised at the large amount of money and wondered what the sailing equivalent would be to circumnavigate the world. “I realized that there must be many people out there who had a boat, but no confidence or had no boat who’d like to achieve this feat. It occurred to me that if I supplied a boat, a skipper and some training and set up a route, some people might be interested. I placed an advert in the newspaper and got over 8,000 replies,” says Knox-Johnston.

“When you get that kind of response and walk away from it, you can be sure that someone else will eventually grab it and run with it, so I established the Clipper Round The World Race in 1996,” says Knox-Johnston. He’s convinced that many aspects of sailing have valuable lessons to teach the international crews that join Clipper from around the world. “One of the most important aspects of sailing is working as a team. This is a fundamental lesson that business can learn from, and help in achieving success. If you work in a large corporation, there’s a good chance you’ll spend most of your time on internal politics,” he explains.

“I’ve worked for two big companies in the past, where someone was always trying to prove they were better than you, by making you look stupid, or trying to block you from doing something. It was very frustrating. “When you’re on a boat, there’s only one focus, and it’s shared by all. We once had the marketing director of Olympus on one of our boats, who said how refreshing it was to see everyone pulling in the same direction for a common cause. Everyone on our boats has an attitude of wanting to win the race together.”

A sales company once placed five of their employees on a Clipper boat many years ago. From working in their own, individual ways, they became a collaborative team after the journey, calling each other up and sharing information about prospective sales. Sales went up 30 percent and the team went on to become an unbreakable force in the market.

While the cost of an 11 month ocean trip being prohibitive for most young people, especially from disadvantaged backgrounds, corporations have stepped in to fund individuals and teams, who’ve realized the life changing benefits of a round the world race and the sense of future confidence it instills in many who would otherwise waste their lives. It has become a viable alternative to sponsoring charities and corporate social responsibility programs, with sponsors seeing a dramatic change in those they invest in.

Clipper has seen people from all walks of life participate, with an amazing 40 percent never having set foot on a boat before. “A fundamental part of being a leader is how you lead people into difficult situations and the preparedness you have around you. This may seem like a simplistic answer on how you train people, but you need to lead people into it in a mannered way. When a squall hits in the middle of the Atlantic you’ve got to be aware of the signs. You can see it in the behavior of the dolphins, the dark clouds on the horizon, watching on the radar.

The result is, that when the squall hits, the boat is prepared, with sails down and speed reduced, and the crew feel they can cope with what nature throws at them. Fear is a natural human reaction but if the boat is ready, people will learn to cope with anything. I could teach this in the classroom but it can never compare to hands-on experience.” “The easy choices in life often offer no pleasure,” says Knox-Johnston.

“It’s the hard and difficult challenges that bring the satisfaction of real achievement. My dream was always to make the globe’s oceans more accessible and to give people the opportunity to do what I had done. Pushing young people especially, into uncomfortable situations, is important. The first thing I might do with a young woman on her first race is to make her climb the mast at sea. This is frightening for anyone the first time and when she comes done I’ll say, ‘well done.’ In many instances this is the first time anyone has ever said this to them in their whole lives.” Many of the young people who race with Clipper are no-hopers, coming from unemployed parents, many from families with two generations of unemployment in the family.

“Two weeks into a race changes them,” says Knox-Johnston. They realize, ‘hang on, I’m not wasted, I’m worth something.’ You’ve changed them, from years of being told they’re useless they feel they can do things. It’s life changing.” Knox-Johnston recalls a woman in one of the first races, who’s company kept her job open for her while she was at sea for a few months. She never returned to work, but instead set up her own company and made twice as much money as her own boss. Once you’ve sailed around the world, in control of your own destiny, it must be difficult to feel that your potential is harnessed by sitting in a desk-bound job in a city. The mutual dependence and trust in fellow crew members has taught participants many lessons. Living together in a confined space, a give-and-take attitude and understanding of those around you are all things that should be found in a good business, too.

“Someone still has to be in charge, though,” says Knox-Johnston. “This is the skipper, who will handpick those he can trust, such as the watch leaders and the engineer or someone to repair the sails, that might change around to give everyone a chance at doing it. Everyone is involved in preparing food.” As in business, the crew looks to the skipper for guidance, as would employees to a CEO. Any signs of panic from the skipper would create panic onboard, and Knox-Johnston’s advice to business leaders on this, during times of turmoil is, “Don’t.”

“Knowing how to run a business, and the knowledge you have about your products and services is good, but knowing how to keep people motivated, happy and wanting to win is equally important.” A good skipper will transfer skills to those onboard, including crucial lessons on how to read the weather, and being 1,000 miles from land means all maintenance has to be done by those onboard. By the end of a typical Clipper race the crew understand how the whole boat works and how to be safe at sea, a confidence builder that sets many participants on a new course in life when back on land. The ocean plays an integral role in many of the Earth’s weather systems and for ordinary people to see and experience this source first-hand, has helped promote respect, and protection for this vital resource.

“Racing is like doing a combination of chess, and pull-ups. It’s about tactics and being able to react swiftly to urgent needs, you can’t sit around and think about it.” One can’t help wondering what benefit this same alertness might have to society and the environment if everyone were to react to the urgent issues in the world today in the same manner.

While Knox-Johnston has concern for the state of the ocean from an environmental perspective, he’s noticed less plastic in the water over the last few years, a sign that legislation might be working. The Marine Pollution (MARPOL) treaty adopted in 1973 and designed to minimize pollution of the seas, has had a positive effect, with hefty fines now in place for transgressors. If you arrive in a U.S. port after weeks at sea and produce one small bag of rubbish, you’re now automatically fined, based on the assumption that the large amount of waste you must have generated over this time has been dumped.

“The other day I was out at sea for an hour and I’m still suffering. The sun is sharper now, why?” he asks. As a man of the sea Knox-Johnston is naturally inclined towards wave energy as an alternative energy source. This is demonstrated in the smallest and most unlikely of ways; the constant rocking of the boat on a voyage actually exercises the body while asleep. Wind energy has been found to be only 17 percent effective and he is convinced that the endless tides are a better source of energy than unpredictable wind conditions on land.

The muscle building and health benefits from continuous movement on the Clipper boats; up to 11 months for those on the full circumnavigation; has sharpened both perception and awareness of all who have raced. The average calorie burn is 5,000 a day, even during rest. Knox-Johnston has seen the unmistakable change in character after a race, an air of confidence about them, regardless of whether they are a CEO or an 18-year-old student.

They’ve done something extraordinary with their lives, and learned about the value of the oceans. “Humans are competitive by nature,” says Knox-Johnston. “Those of us in business need to be, or we won’t succeed. It’s how we manage the challenges of teamwork and mutual respect along the way that will determine our success.

My challenge to you is simple – dare to dream – because something as huge as this starts with just that. If you follow that dream, who knows where you’ll end up.”