- Marc Dullaert, a successful businessman from Europe, witnesses a death in Africa and decides that he can no longer be a spectator to the world’s suffering.

- Moved by a 14-year-old’s campaign to stop child labor, he wonders why a child cannot win the Nobel Peace Prize.

- A meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev results in the establishment of a peace price for children.

- Children make up half the world’s population, yet are seen as second class citizens. Dullaert has shown how winners of the Children’s Peace Prize can influence key adult change makers and global institutions of influence.

One morning on the border of Sierra Leone I was woken by an awful sound. It sounded like an animal in distress. I stepped outside and saw a mother from a nearby refugee camp holding her child that had passed away. I was filming documentaries for my television production company and our vehicle had broken down the day before, resulting in us sleeping on the passenger seats. It was an incident that was to change my life forever. Seeing that mother holding her dead child was like being struck by lightning and I knew that I had to do something. I phoned my wife as soon as I got a signal, she designed a logo and I came up with a name: KidsRights. We started with a small project to benefit Aids orphans in South Africa and then steadily added more. It resulted in me selling my business, a large production company that produced shows for 12 European countries, to enable me to focus entirely on building KidsRights.

In 2004 the Children’s Peace Prize was born. I watched the announcement of the new Nobel Peace Prize winner on the evening news one evening and shortly afterwards a documentary on an 11-year-old boy called Iqbal Masih from Pakistan. Masih had organised a protest rally with thousands of children to protest against working conditions within the tapestry industry, basically children working in sweat shops. I was so impressed that I asked myself, “Why can’t a child win the Nobel Peace Prize?”

I made contact with the Oslo Nobel Peace Prize Committee, who were very kind but said, “Sorry Mr. Dullaert our statutes are more than 100 years old and we will not change them. The Nobel Peace Prize is not for children.”

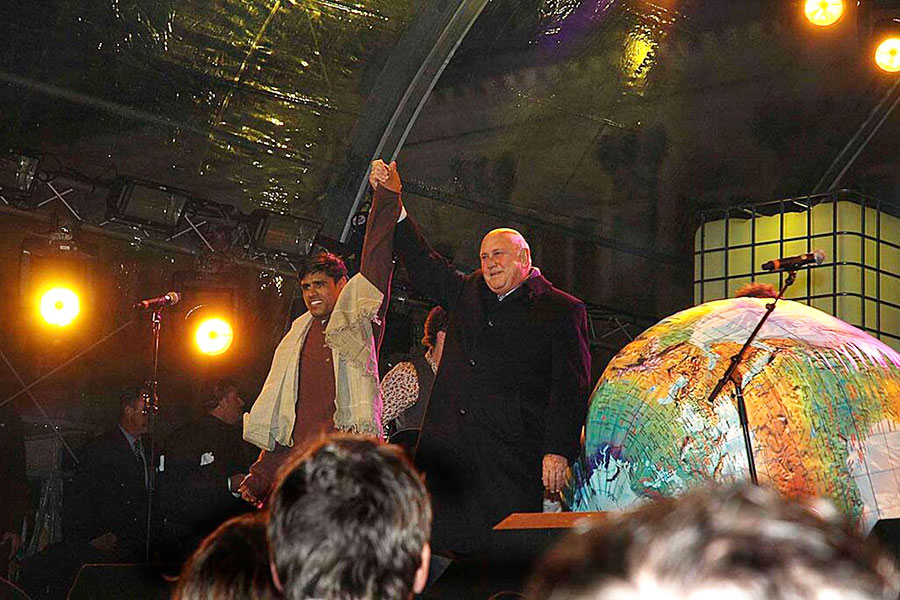

Then I heard about the yearly gathering of Nobel Peace Prize winners, chaired by the former president of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev. I managed to secure a ten-minute meeting and met him at the Gorbachev Foundation offices in Moscow.

I tried to explain to him my idea of an international children’s peace prize, but despite being friendly, he didn’t speak English and the translator wasn’t helping much either. Gorbachev sat looking at me unblinking. I was getting nowhere. Suddenly, in desperation, I asked, “Mr. Gorbachev, do you have grandchildren and do you think you could learn something from them?” It was an icebreaker. He suddenly became emotional and started talking about his daughter and grandchildren. After my short interview, I was sent outside to wait for his answer – 45 minutes in a cold corridor, like a punished school child. I was eventually summoned back into his office and Gorbachev said, “Yes, let’s do this.”

The first International Children’s Peace Prize was launched at the 2005 peace summit in Rome and the first winner was South African Nkosi Johnson for his fight for the rights of children with HIV/AIDS. It was awarded to him posthumously as he had died of HIV/AIDS himself four years earlier at the age of 12. Ten years later, we now reach more than 1 billion people around the world when we acknowledge a child with a peace prize. The statuette they receive literally depicts a child moving the world because I strongly believe that children can be change makers. Sure, children are vulnerable, but they also harbor enormous strengths.

The Children’s Peace Prize provides a platform for children to voice their opinions and to inspire other children to bring about change. It can generate enormous impact. For example, Om Prakash Gurjar won his peace prize for freeing 500 children from slavery in India. He appeared on BBC news and when Gordon Brown, then U.K. minister of finance, visited India shortly after he requested a meeting. He was so impressed with Gurjar that he gave the Indian government £200 million to start eradicating child slavery and illiteracy. This demonstrates the power of a 14-year-old. After awarding the peace prize each year we can see the positive effects rippling out – it’s like throwing a stone into water.

However, exposure can also have a downside. In 2011 we got a handwritten letter from a schoolteacher in Pakistan, telling us about the remarkable story of a girl called Malala Yousafzai. She had stubbornly refused to stop her schooling, and despite being threatened by the Taliban, had continued advocating for girls education in a very public and courageous way. We wanted to award Malala the Children’s Peace Prize but were concerned for her safety, so we decided to nominate her instead – giving the prize that year to Chaeli Mycroft, a girl with a disability from South Africa.

The president of Pakistan was disappointed and he announced a few days later a National Peace Prize for Pakistan. It was awarded to Malala and she was thrust into the international limelight. The Taliban shot her a few months later. We could never have imagined that nominating her for a peace prize would trigger these series of events. The irony is that this tragic event led to her getting even wider exposure. She received the International Children’s Peace Prize in 2013 after all, and one year later received the renowned Nobel Peace Prize.

What’s become clear is that children who win the peace prize can positively influence key adult change-makers. In 2007, The Elders was formed – a group of international leaders working together for peace and human rights. We decided to create the youth equivalent – The Youngsters. One of our winners, Thandiwe Chama has addressed the United Nations on the upcoming Sustainable Development Goals. Baruani Ndume from Tanzania, has addressed world leaders on what it’s like to be a child refugee and victim of war. Our winners have become ambassadors for good.

Children make up more than half the world’s population and are citizens of countries, despite being treated like second-class citizens. Many leaders and politicians pay lip service to children and jump at opportunities to have pictures taken with them, but they don’t take the time to listen to them. I’m not saying that young people know more than adults, just that they have a different view of the world. The least we can do is consult them when making laws or policies that directly affect them. One of my biggest eye-openers has been to see this happening more in Asia and Africa than in Europe – where it’s still very difficult to find real participation by children.

But, while children are capable of tackling tough social challenges and showing adults new ways of seeing the world, we still need to nurture an important ingredient of childhood – love. At one of our projects in India I once spoke to a boy who’d been freed from slavery. The kids were given a daily cooked meal and I said he must be very happy with that. He looked at me and said: “Of course I’m happy with one warm meal, but it’s more important to know that somebody cares for me.”