Voice computing will profoundly reshape the way humans relate to machines. Rather than allowing a sense of alienation to creep in, some organizations have appropriated the technology to capture fading stories and bring them back to life for future generations. Instead of writing a letter or recording a video for your great-grandchildren, you may one day leave a digital replica of yourself behind.

The emergence of voice computing interfaces represents the biggest technological disruption since the smartphone. Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant are becoming the new universal remotes to reality, upending multibillion-dollar business models in Silicon Valley and beyond. Today, though, most of what people do with voice devices is fairly prosaic — setting timers, playing music, and asking basic, factual questions.

In the future, however, one of the most dramatic applications of voice technology will be to enable what’s known as “virtual immortality”— the creation of digital replicas that live on after the real people who inspired them have died.

For a glimpse of this future, consider a groundbreaking project called New Dimensions in Testimony. A joint effort by the Institute for Creative Technologies and the USC Shoah Foundation, the project aims to memorialize Holocaust survivors.

In 1943 the Nazis captured a 10-year-old boy named Pinchas Gutter and his family and imprisoned them in concentration camps. Gutter’s sister and parents were killed in the gas chambers before he could even say goodbye. He would go on to be beaten, shuttled between different labor camps, and put on a death march before finally being freed by the Red Army in 1945.

Gutter, now in his 80s, has devoted himself to sharing these horrors, giving talks and answering questions. But like all of the remaining Holocaust survivors, Gutter will not be around much longer. Testimonies like his have, of course, been captured in print, audio, and film. But telling a story in person has unique power. As Rabbi Marvin Hier, the dean and founder of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, once explained, “There’s nothing like the human witness who can look you in the eye and say, ‘Look, this is what happened to my husband. This is what happened to my children. This is what happened to my grandparents.’”

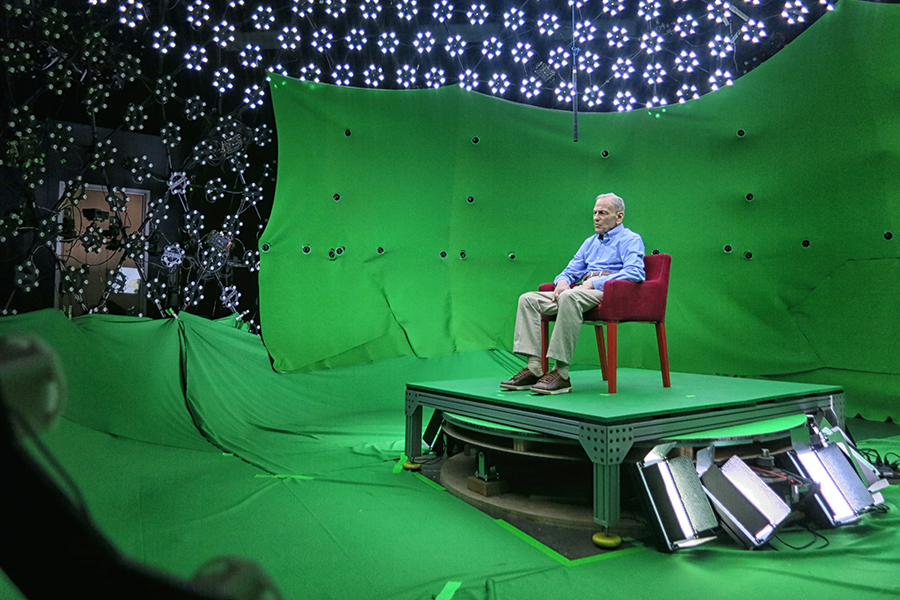

Targeting the immediacy of in-person storytelling, the New Dimensions team interviewed Gutter and more than a dozen other Holocaust survivors, asking them hundreds of questions in multiday sessions. The interviews took place on a soundstage inside of what looked like a giant geodesic dome. Mounted on the inside of the dome were thousands of tiny LED lights and 30 cameras recording the survivors from every angle.

Using visual-effects technologies that were originally developed for military training simulators and movies such as Avatar, the project’s scientists transformed these recordings into movie clips, which, when projected onto a special screen, appear to be three-dimensional. As holographic display techniques continue to improve, the scientists will be able to create even more lifelike holograms. They could project Gutter or another survivor into any room, illuminate him as if by the ambient lighting of that space, and allow people to walk around him. Paul Debevec, a professor of computer science at USC, says that the goal is to make it “seem like they are sitting in the same room as the audience.”

ICT’s conversational-AI experts, in turn, created a natural-language system to interpret what people were asking about

and retrieve an appropriate answer in the digital version of the survivor’s brain. Those answers might be short but often are many minutes long. The system is currently being displayed in museums around the United States.

David Traum, an ICT computer scientist, says he believes that interactive preservations of the dead will become widespread in the future. If the price of the technology comes down enough, ordinary people may keep versions of their late relatives around.

Fritzie Fritzshall, another Holocaust survivor who participated in the New Dimensions project, is a believer in the technology. Most of Fritzshall’s family perished in concentration camps, forever silencing their voices. Fritzshall, too, will die before long, and she says she is glad that her digital double will continue to share her narrative. “I have passed it on to my twin, so to speak,” Fritzshall told a journalist. “When I’m no longer here, she can answer for what’s asked of me. She will carry on the story forever.”