In the sunny outdoor restaurant of a small country hotel, a former guerilla commander and a wealthy businesswoman greet each other by name.

The workshop organizer tells them he’s surprised they know each other. The businesswoman explains: “We met when I brought him the money to ransom a man who’d been kidnapped by his soldiers.” The guerilla adds: “The reason we’re at this meeting is so that no one will have to do such things again.”

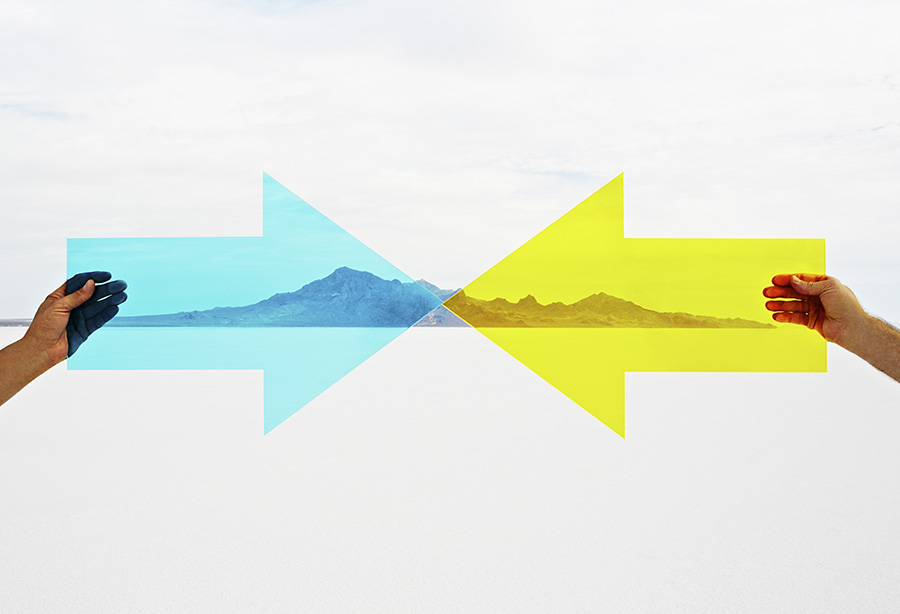

How did these two very different people come together to solve their shared problem? A process called transformative facilitation enabled this breakthrough.

The workshop they attended brought together a diverse group of leaders to talk about what they could do to transform their country. Seventeen months earlier, in June 2016, the government of Colombia and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia guerillas had signed a treaty to end their 52-year war. Thousands had been kidnapped, hundreds of thousands killed, and millions displaced.

After decades of being at one another’s throats, Colombians were now trying, amid much turmoil and trepidation, to break through and work together to construct a better future. Our workshop was part of this effort.

The beginnings of their collaboration

In January 2017, in the troubled southwest of the country, two civic-minded leaders, Manuel José Carvajal, a businessman with connections to the elite, and Manuel Ramiro Muñoz, a professor with links to the grassroots, decided to organize a project to contribute to rebuilding the region’s society and economy.

Their idea was to bring together leaders who were representative of the region’s stakeholders: everyone with a stake in the area’s future and, therefore, an interest in making it better. They recruited 40 influential people from different sectors—politicians from opposing parties, former guerilla commanders, businesspeople, nonprofit managers, and community activists—who, if they could collaborate, could make a real difference in the region.

In November 2017, the first workshop of this group took place over three days at the country hotel. On the morning of the first day, the participants were tense. They had significant political, ideological, economic, and cultural differences—and significant disagreements about what had happened in the region and what needed to happen.

Some of them were enemies. Many of them had strong prejudices. Most of them felt at risk in being there; one politician insisted that no photographs be taken because he didn’t want it known that he was sitting down with his rivals. But all of them showed up anyway because they hoped the effort would create a better future.

To work together, the participants needed to create enough of a common language to be able to talk about the situation and how they could change it. We started by conducting open-ended interviews with every participant to enroll them in the project and hear their views on the key issues facing the region. We then compiled these views into a report containing a selection of their unattributed, verbatim statements, which we distributed in advance of the first workshop.

Our methods

On the first morning of the workshop, participants presented their perspective on the current reality of the region, along with a physical object they had brought (these included a stone, a book, a seed, and a machete), which produced fresh, symbolic images. They used toy bricks to build models of the social-political-economic-cultural system of the region in its larger context, enabling them to share and combine their different tacit understandings visibly and fluidly. And they wrote and organized their ideas on sticky notes, helping create and iterate their composite understanding of the current reality.

These methodologies created space for all the participants, including minority and marginalized ones, to express themselves equally and openly and make visible some of what had been invisible.

Most crucially, the participants needed to be willing and able to work together. To support them in connecting better with one another, we:

Agreed on a set of ground rules, especially about confidentiality, which helped them feel safer to make their contributions.

Ate our meals together at long tables, which created a space for informal conversations.

Invited them to go on walks in pairs, which enabled the development of personal connections across divides.

Introduced a framework for open, nonjudgmental, empathetic listening, which they practiced in pairs; the final step in this exercise involved looking into their partner’s eyes, and the unfamiliar and unexpected sense of connection in the room was palpable.

Facilitated an hour during which the participants told personal stories about their lives, which enabled them to understand better why some of them had ended up on opposing paths.

This approach—though unconventional—enabled the participants to contribute and connect equitably, and it helped this deeply polarized group move forward.