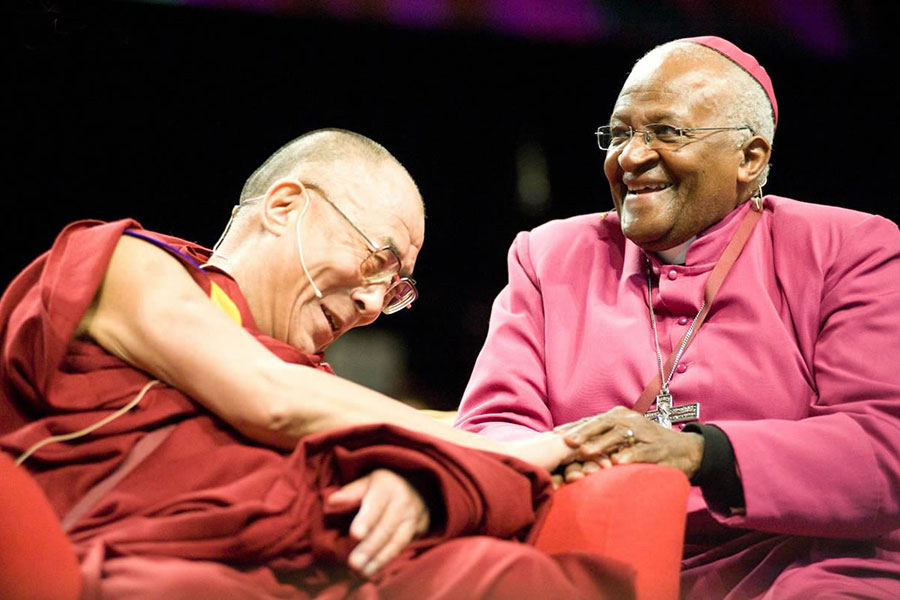

In this exclusive interview with Real Leaders, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and social rights activist Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu says he is not threatened by the beliefs of others. He believes the world should become more aware of our shared humanity to avoid future conflicts.

You represent a very specific world view, Christianity, yet have managed to mediate between opposing belief systems and make people aware of their common humanity. How have you managed this?

It doesn’t matter where we worship or what we call God; there is only one, inter-dependent human family. We are born for goodness, to love – free of prejudice. All of us, without exception. There is greater commonality in our belief systems than we tend to credit, a golden thread expressed in the maxim that one should treat others as one would like others to treat oneself. I don’t believe in the notion of “opposing belief systems.” It would be more accurate to say that human beings have a long history of rationalizing acts of inhumanity on the basis of their own interpretations of the will of God.

In your view, what does the world need more of in order to become more peaceful?

Our failure to recognize the humanity in others lays the foundations for selfishness rather than selflessness. It leads to gross inequity and hideous disparities in qualities of life – and, often, the degradation of environments in which relatively poor people live. A world that recognizes the equal worth and vulnerabilities of all its people will be a much more peaceful place.

Has the role of religion changed over the last 10 years?

Peoples’ interpretation of religion can change, but I don’t believe the role of religion is changeable. Religion does not just concern one’s personal relationship with God; it’s more about the manner in which we interact with others – about our broader responsibilities to the human family and the earth we share.

Figures suggest many young people are turning away from the church. Is it possible to be a good human being without being religious?

Much as I’d love to see all the world’s churches, mosques, synagogues and temples overflowing with humanity, how good we are is not measured by the number of times we attend formal religious ceremonies. Among the most heartening trends I have noticed on my travels over the past dozen or so years has been the spiritual strength of young people. They don’t necessarily occupy the front pews on Sunday, but they seem to have been born with an enhanced sense of tolerance and a deep understanding of our inter-dependence, on each other and a functional world.

The phrase “One man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist” has been used by various people and political groups across the world to justify their actions. How do you reconcile such opposing viewpoints in people who are all convinced they are fighting for freedom?

Many have argued that people committing acts of violence in pursuit of just objectives should be regarded as freedom fighters, not terrorists. Nelson Mandela is a leading recent example of this dual identity. He was undoubtedly a freedom fighter who, at a particular stage in the struggle against apartheid, concluded that non-violent means of struggle were failing to achieve democracy and convinced his organization to take up arms. Although the resistance army that he commanded initially targeted infrastructure, rather than people – and was ultimately of significantly greater symbolic than military value to the liberation cause – Mandela and his comrades were branded terrorists at home and abroad.

I don’t believe there is ever a valid justification for violence, it only begets more violence. Where people are not free they should struggle for their freedom through non-violent means. In the 1970s and 1980s, with the help of our friends abroad, South Africans developed a non-violent toolbox of boycott, sanctions and divestment. Together with mass resistance – people swimming together in pursuit of a righteous cause are unstoppable – we brought the apartheid state to its knees.

What role should business be playing in solving serious social issues?

Corporations have wider responsibilities than enriching their shareholders; the pursuit of profits “at any cost” to people and the environment is morally bankrupt and destroying the earth. By considering the effect of their enterprise on others, and embracing a sustainable and more equitable future, corporations become active agents for social change, for societal good. It is not charity or philanthropy that I’m speaking about, and it goes beyond corporate social investment.

It’s about the necessity of developing a world in which all feel valued, in which the dignity of all is taken into account. It’s the new way of thinking: Practice it at home and unleash it in your communities, your organizations, associations and boardrooms. Consider it in your negotiations and your contracts. Consider the effects on others. This consideration will not just benefit others’ (though there’d be nothing wrong with that!). It will benefit all in the village. Conducting business ethically need not equate to a reduction in profits.

Was there a personal “aha” moment growing up, when you realized that you wanted to make a positive difference in the world?

The closest I can think of to an “aha” moment occurred in my childhood, when a white priest greeted my mother politely in the street. The same priest, Father Trevor Huddleston, later visited me regularly when I nearly succumbed to tuberculosis. He taught me invaluable lessons about the human family; that it doesn’t matter how we look or where we come from, we are made for each other, for compassion, for support and for love. I called my son Trevor, and Bishop Huddleston, as he later became known, went on to lead the International Anti-Apartheid Movement.

What makes you the most frustrated and angry?

I get frustrated when people fail to achieve their potential, or get in the away of others reaching for their dreams.

What makes a good leader?

In his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela told of the lessons about leadership learned in his youth from the acting King of the Thembu people, who was his guardian following the death of his father. He described how King Jongintaba would always listen to the views of everyone else present before speaking himself. Mandela compared good leaders to shepherds walking behind their flock. The sheep think they are following the one in front of them, when, in fact, they’re being directed from behind. But there were times that required the shepherd to walk out in front. His secret decision to initiate talks with the apartheid government was such a time, he wrote. Mandela’s lessons about leadership are applicable to all spheres of life. They are based on a consideration of the views and dignity of others.

What is the key to overcoming future conflicts?

The key to overcoming conflict is to treat others as we would have them treat us. Or, conversely, not to treat anyone as we would, ourselves, not wish to be treated.