Grown adults dangle from hanging chairs bolted to the ceiling. Young executives in T-shirts and jeans are barely visible inside giant, brightly-colored beanbags scattered on the floor, and a woman on a skateboard weaves through the desks while speaking on her mobile phone.

The CEO arrives downstairs for a meeting by sliding out of a large, red plastic tube, like the one you’ll see at a waterpark. You might think you’ve walked into a kindergarten – or an institution for the criminally insane. But this is the office of the world’s second most valuable company – Google, a company that has influenced what we know, how we do things and how we value our goods and services. The phrase “to Google” has become part of our everyday vocabulary, to the point where Google worries they might someday lose their trademark rights if the phrase becomes too generic.

The search engine has become an external brain that allows us to magically learn things when we type into a search bar, looking for facts, figures and the meaning of life. It has become such a part of our conscience that medical staff regularly complain that “Dr. Google” has become the first place to visit rather than the doctors rooms at a hospital.

And if I hadn’t Googled the phrase, “Google’s market worth” you wouldn’t know that the company’s brand value is today worth USD82.5 billion, and also listed as number two on America’s Best Employers List.

It’s a company that encourages crazy thinking, with very few rules, and has ushered in a new era of business that prizes collaboration over competition.

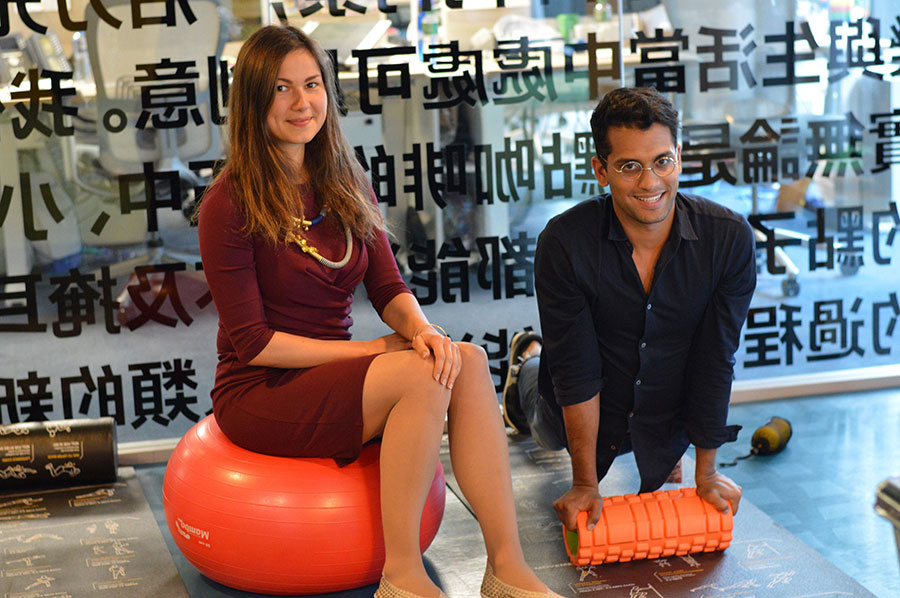

Caro Schulz and Sameer Rawjee work in the Google office in Dublin, Ireland, and some of this big thinking and “craziness” has rubbed off on them. The twentysomethings have decided to relook how we educate ourselves and what it means to become “qualified” for the workplace – in a world that changes every few weeks.

Spotting a gap in the market, they founded O School, an institution that ignores narrow qualifications and focuses on providing a more well-rounded, holistic learning experience. Schulz, whose business card shows she’s in charge of “mindfulness and wellbeing” at Google (along with sales) is originally from Germany and saw a need for innovation and something new in the education space, along with partner Rawjee.

“Not so long ago we were both students and we saw how people struggled in the business world with a few key things that were missing,” says Schulz. “We should be educating the full human being, not just the intellect. Let’s call it intuition.”

Emulating Google’s free-thinking, teamwork approach to innovation, the pair have pulled together a diverse team that would look out of place in most boardrooms: A Buddhist monk from Oxford, England, a martial artist from the Virgin Group, a psychologist from South Africa, a cell renewal expert from beauty company Weleda and a musician from the United Nations. When Schulz and Rawjee talk of “well-rounded,” they mean it.

Their time at Google has shown them that life is about more than work; a main catalyst for them to create O School. Due to launch in Dublin and South Africa in 2017, the schools will offer a physical space where people attend in person. In an era of online learning, this may come as a surprise, but the pair have based this decision on extensive research within Google itself. “When we asked people our age if they would put their kids in front of a computer for their higher education, they said ‘no,’” says Schulz.

“We still need great technology but we also need to see ourselves as a connected community of real people.”

“There are many people studying at university right now who are focused on solving societal challenges,” adds Rawjee. “While this is important, our big gamble with O School is what we call holistic intelligence: Engaging mind, heart and hand.” To illustrate the point, Schulz suggests that instead of studying, say, economics and art, as two separate disciplines, we should rather be studying how economics and art relate to one another.

So what future jobs, exactly, will they be preparing young people for?

“Many companies have started hiring people with an education in more than one field,” says Rawjee. “Instead, they are looking for generalists – people who are educated on a wide range of subjects. We can’t foresee the jobs of the future so education must produce people with the agility and flexibility to adapt to change fast. Yes, specialize in one or two fields but also have the ability to connect dots across many disciplines.” At Google, every prospective employee goes through six interviews, each with different people. It’s employment by consensus and you’ll be asked some funny questions, like: “What do you want to achieve in the world?” – all aimed at getting a picture of the whole person.

“When people ask, ‘What was I made for in life?’, it shouldn’t feel as if the answer is something you pull from a lucky packet,” says Schulz. “What you’re meant to do comes from connecting the dots in your life, looking back and seeing what was meaningful at an early age. Steve Jobs spoke of this all the time.”

Millennials now demand purpose in a job and traditional business models will find it increasingly difficult to attract talent without changing their thinking. Schulz paints the future of the workplace: “Employees will get to change careers every year and be allowed to determine what their futures will look like soon after joining. There is no longer a 10-year climb up a corporate ladder and employers will finally acknowledge that you have a family life beyond work. The two most important days in your life are: when you are born, and when you know why you were born,” says Rawjee. “We want to attract brilliant, intelligent thinkers that have nothing to do with grades. You can’t value people with past metrics anymore.”

Sometimes the difference between success and failure depends on your ability to spot an opportunity when it presents itself. In 1999, for example, Excite turned down an offer to purchase Google for USD1 million and in 2002 Yahoo decided they weren’t willing to pay more than USD3 billion for the young Internet search firm, and walked away. The rest, as they say, is history.