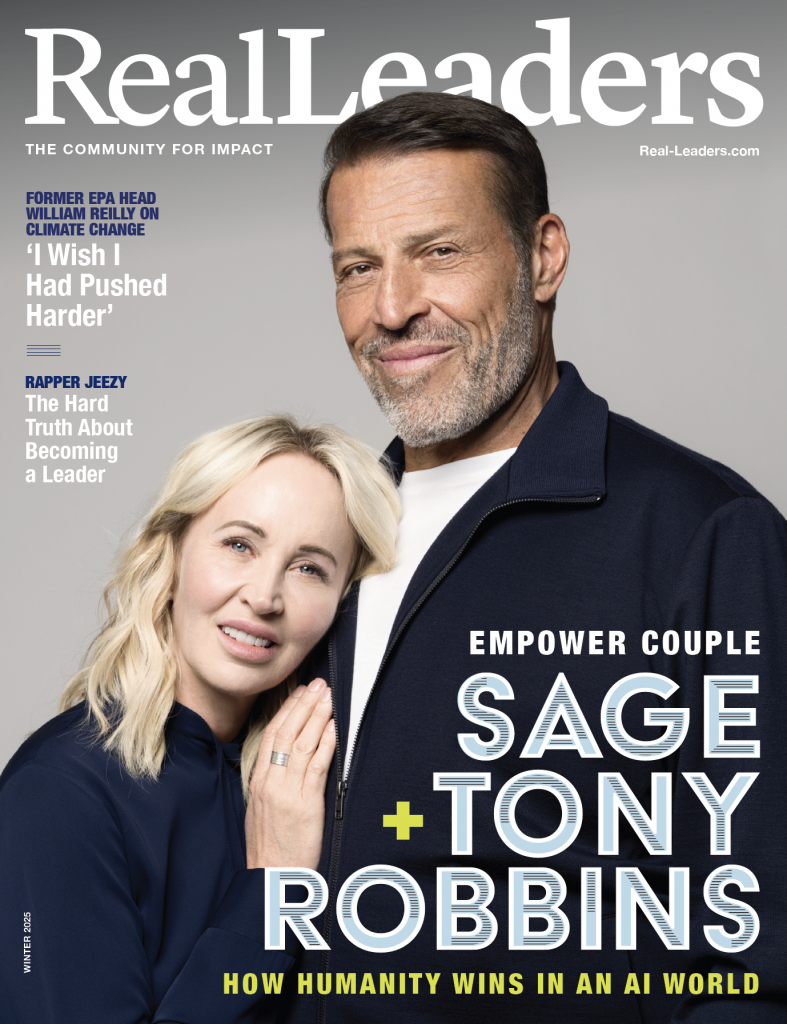

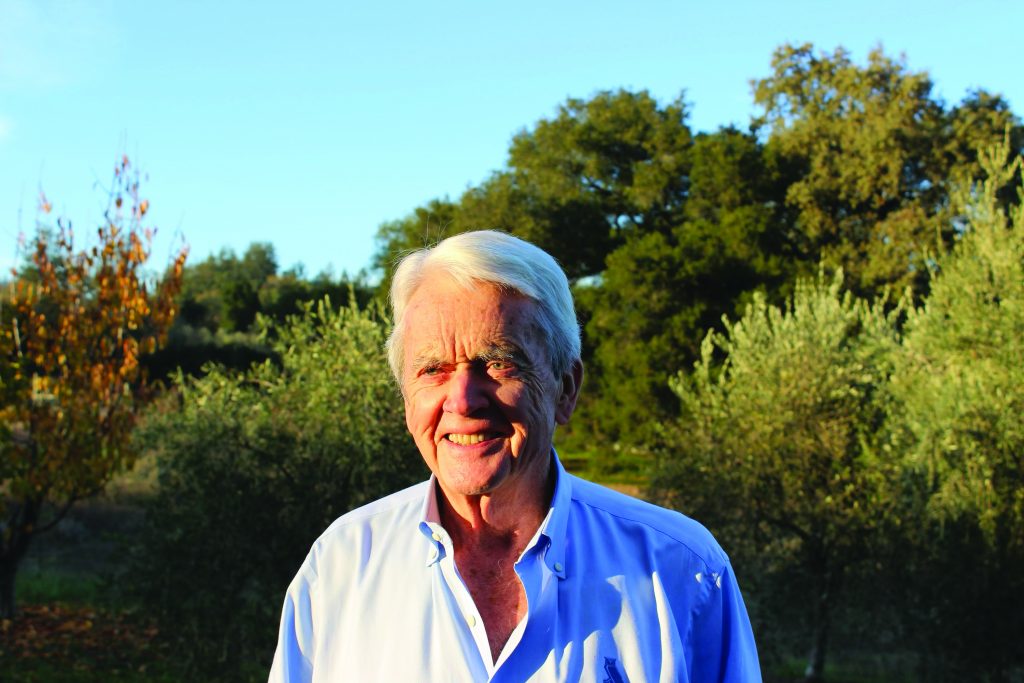

In the twilight of his career, Reilly ruminates over the climate change road not taken — but it’s not over yet.

He had direct access to a sympathetic president of the most powerful country in the world but struggled — he might even say failed — to secure the most critical planet-focused agenda of our time: the battle against global warming. Now it’s all coming to light in a documentary about why the U.S. walked away when the rest of the world was poised to stop the climate crisis.

Head of the Environmental Protection Agency from 1989–1993, William K. Reilly was asked to share intimate details about the behind-the-scenes battle that shaped the nation’s stance on climate change for a film called The White House Effect. With screenings around the world for the last 12 months, the documentary surfaced a host of memories and a deeply personal contemplation of his role in what Indiewire describes as “the quiet tragedy about how we let our planet slip away.”

Directors Bonni Cohen, Pedro Kos, and Jon Shenk focus on the pivotal years of the George H.W. Bush administration, when scientists were desperately trying to educate people about global warming. Bush promised to use “the White House effect” to face the issue head-on and create a plan to get it under control. The documentary reveals how Bush finds himself wedged between Chief of Staff John H. Sununu and industry powerhouses on one side and Reilly and climatologists on the other. The White House Effect explores how, when faced with tremendous pressure to make a decision, the United States undermined a global agreement at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit that set aggressive limits on emissions — and changed history.

“I was not thrilled to hear a movie was being done on one of my biggest disappointments, but they got it right,” Reilly tells Real Leaders. “They treated Bush as a serious man whose reasons for doing what he did were quite plausible. It was clear that the directors were not chasing headlines. They were extremely careful.”

For the making of the documentary, Reilly gave interviews and shared thousands of pages of notes from his years serving the White House and the American people as its chief environmentalist. His personal stories from that time feature an all-star cast: Bush, Sununu, James Baker. The plot? Tackling global warming in a country divided on the issue. The villain? Senior leaders in a presidential administration who didn’t stand with the rest of the world on climate change. The hero? Well that’s the problem. Reilly wonders if it should have been him.

He certainly had his share of triumphs — founding Aqua International Partners, an investment group that serves the water and renewable energy sectors; leading the World Wildlife Fund with over 1 million members; heading the EPA, where he employed over 18,000 people and managed a $7-billion budget; and overseeing amendments to the Clean Air Act, including an emissions trading program to cut acid rain. Reilly also fostered innovative technologies for cleanups, breathing new life into the Superfund program and raising billions of dollars through tough enforcement regulations.

But as heroes often do, Reilly questions whether he should have — or even could have — done more to ensure the U.S. took climate change more seriously and acted with the rest of the world on what the science was saying.

Science — that was also part of the problem, says Reilly. While he was able to strengthen the role of science at the EPA, securing the adoption of “green” provisions in the North American Free Trade Agreement and asserting environmental priorities in U.S. foreign policy, the sad truth is that the need to protect our planet became politicized.

Reilly says the fossil fuel industry, for example, was quite calculating in the way it dealt with the climate issue. “They got advice from their lobbyists not to disparage the science behind climate change but to simply point to the facts and say that it’s uncertain and that scientists have not really agreed,” says Reilly. “The scientific community would not attribute any specific heat wave or great storms or hurricane frequency to climate change, so that played into it too. It was a smart political strategy: ‘Don’t say it isn’t true. Just say it isn’t proven,’ which basically meant they didn’t have to step back on fossil fuels or support a change in our lifestyle. Environmentalists, frankly, were mistaken in repeatedly shouting from the rooftops that climate change requires a transformation of the American way of life. I don’t think the public wanted anything to do with what sounds like a transformation of their way of life.”

Just prior to his service in the Bush administration, Reilly says people could talk about nothing else but climate change. “It was a hot summer in 1988,” he recalls. “Medical waste had washed up on the beaches of New Jersey. There were records set in city after city for pollution problems connected to the very heavy heat, and it was quite clear that Bush’s statement that he would bring the White House effect to bear on the climate effect was extremely important politically. Everybody’s mind was on climate change, and the press was covering it every night.”

Reilly says the documentary captures the arc from high public concern around climate change to utter disinterest four years later, when the headlines turned to the economy and jobs. “It’s quite clear that they made the right call to switch focuses from a political point of view,” says Reilly. “People could see their friends losing jobs, but climate change was more of a future problem.”

Reilly says everyone close to Bush urged him to focus on the economy. “Everyone except me and National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft,” he recalls. “We thought Bush should join the rest of the developed world and focus on climate change. Bush had promised stabilization of greenhouse gases, but he was the only major world leader who didn’t press it. He dropped it when he saw the way things were going at home.”

The documentary, Reilly says, accurately portrays how Sununu isolated the president from any real scientists. “Bush never met with the National Academy of Sciences, for example, and the movie made clear that Secretary of State Jim Baker was always friendly toward me and had delivered a very supportive speech about the climate problem, but the chief of staff warned him off. Baker recused himself from the climate issue, and he sent word to me, ‘Tell Reilly he will never beat the White House,’ which was his way of saying to drop the climate issue.”

The documentary gave Reilly a chance to reflect on that time and process its most important lessons. “One of my lessons from this experience is stay with the issue, whether you’re losing or not. You could still have an impact, and at least historically, people would see that we did have the information. We did have cause to do something that we chose not to do.”

Secondly Reilly learned the importance of acting on opportunity when it comes. “If you don’t seize it, it may have consequences you don’t anticipate,” he says. “When you’re doing important work, drive it hard. Realize those moments for what they are and take great satisfaction in them because it may never come again in your career.”

Highs and Lows

During an interview at the end of the documentary, Reilly reflects on a conversation he had with George Mitchell, senior majority leader at that time and a strong environmentalist. “I asked him, ‘If Bush had made a different decision to stabilize or reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, and we put that into a legislative proposal, could it have passed?’ He said, ‘No, you could not have beaten Dingle in the House and Byrd in the Senate and the coalitions they had.’ Then he quickly added, ‘But I would have said the same thing about the Clean Air Act, and you did win there. You defeated them on that, but I don’t think you could have done it again.’”

Over the years Reilly has thought a lot about why the American public doesn’t always take climate change seriously. He points out that while people could see air pollution in the late 1960s and early 1970s, climate change is imperceptible on a day-to-day basis. “For so long scientists have been unwilling to attribute special episodes of heavy heat to climate change,” says Reilly. “They said it’s consistent with what the science tells us to expect, but they couldn’t trace it directly. It took a long time for the scientists to resolve altogether that humans are causing this. I knew they had essentially resolved it during our time in office. The National Academy of Sciences reported twice on climate change, so we had enough science, and that bothered me a lot.”

The truth is, he says, that many industries are completely aware of climate change, but to acknowledge it publicly would result in more regulations and the need to conform to new, more costly practices. “That’s why Al Gore calls it an inconvenient truth,” says Reilly. “Many people don’t want to acknowledge climate change to protect their own economic interests.”

In preparing his memoir Reilly has had the opportunity to think about the highs and lows of his career. His high point was the signing of the Clean Air Act amendments, which Reilly describes as path-breaking due to its use of market-based incentives, the fact that it was a permit-based system with sensors in the smokestacks that sent data straight to EPA, and that it had very significant fines for overages.

“If you exceeded your emissions limit, you had to buy the rights from another company that had reduced its emissions more than the requirement,” Reilly explains. “It was a very efficient market system. The Office of Management and Budget predicted that the cost of the clean air and acid rain requirements would be about $1,400–$1,600 a ton. It ended up being less than $100 a ton because of the efficiency of the market design.”

He remembers his career low very clearly. He was head of the U.S. delegation to the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in June 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. “I got up to deliver the statement for the United States, and I remember walking toward the platform thinking, ‘This should have been the high point of my career, but it’s not.’ I couldn’t talk about the biodiversity convention — which we were refusing to sign — or the climate convention, which was our idea, but we were refusing to put teeth into it by not making the commitment to reduce greenhouse gases. So I talked about the magnificent work the EPA was doing cleaning up Eastern Europe. There were a lot of Eastern European countries who were very pleased with that statement, but it wasn’t the statement I wanted to give. It was a real disappointment.”

Reilly says he overanalyzed whether there was anything he could have done to change Bush’s mind on greenhouse gas stabilization. “Given that I was all alone on that, I don’t think so,” he admits. “The vice president, senior staff, the Council of Economic Advisers chairman, the science adviser — they were all on the other side of the issue. I don’t think it’s reasonable to think that I could have, but I have thought about it for decades.”

For example he wonders what might have happened had he gotten Helmut Kohl, chancellor of Germany who was very respected by Bush, to call the president. “During a meeting in Germany, Kohl looked me square in the eye and said, ‘On your country and mine depends whatever hope this planet has to avert a catastrophe of climate, and on your shoulders, Mr. Reilly, rests the responsibility for bringing your president to understand the significance of this decision and of this issue.’ I knew how passionately Kohl cared about climate, but I didn’t use that card. I didn’t try to get Kohl involved, and I’ll never know whether it would have made any difference.”

Another important factor in America’s stance on climate change is that all of this was unfolding during an election year. “Tommy Koh, a Singaporean diplomat, said that a very important lesson from this conference is never schedule a conference of international significance within an American election year,” recalls Reilly. “I thought that was very shrewd, and it’s true because in an election year we are much more vulnerable and sensitive to the politics than we would be otherwise.”

Business in Politics

Reilly doesn’t think it’s a bad thing that more business leaders are getting involved in politics. “There is a shift in the country toward protecting the environment, and businesses know that,” he says. “Renewables are making the case for themselves.”

Reilly admits he was at a real low point after the first two months of the Trump administration. “He basically destroyed a number of things I personally initiated, like the Office of Environmental Justice, EPA, and ENERGY Star. It has been proposed to defund a whole series of regulations on cars and trucks. I was pretty unhappy and wasn’t sleeping very well.”

But Reilly found his inspiration again last April at the 2025 William K. Reilly Leadership Award presentation at the Center for Environmental Policy, School for Public Affairs, at American University. Research scientist award-winners Gretchen Goldman and Adrienne Hollis were recognized. Before the ceremony, Goldman taught a class that Reilly attended. “There were probably 40 or 50 students, and the energy in that class was electric. You could feel it. It was crisp, excited, and ambitious,” says Reilly. “I was so taken by their energy, their enthusiasm. They were not preoccupied with all the destruction of the environmental apparatus. They asked me for advice on finding environmental careers.”

Reilly told the students that while many environmentalists work at the federal government, most states have environmental problems and need their help. He shared a story about a young environmentalist from Kentucky that he met at a Yale University symposium. “She said that never until the first Trump administration did Kentucky establish a series of environmental priorities and responsibilities, which the state had never thought was in its purview. She said because the federal government was not doing anything on climate or the environment, the state decided to take it on themselves. She said Kentucky never had a more creative and productive period than the four years of the first Trump administration. And I was quite taken by that.”

Reilly told the students, “We’re about to see if the states can step up to this challenge. Many states have built a great record on the environment over the last 50-plus years since Earth Day 1970, and they’re going to want to keep it. That’s where you will find your jobs.”

Soon after at a screening of The White House Effect at Yale University, Reilly was inspired again by the students’ questions. “It’s not a very hopeful movie because things didn’t come out well for those of us who wanted a response to climate change,” he says. “But the students thought that I had really stayed with the issue, which surprised me. I said, ‘I think you should learn from that. It’s not over when you lose a big decision. It’s not over. Look for your day to come again and work for it.’”

Reilly, 85, has given much thought to what he wants his legacy to be: He hopes the next generation will draw from his lessons and boldly champion the charge against climate change — with no regrets.

A New EPA? Opportunity to Right Some Wrongs

Reilly recently gave a keynote speech at the EPA Alumni Association Annual Meeting with an insightful message: The decomposition of the EPA by the Trump administration gives environmentalists a chance to fix what is broken. “The EPA’s creation and structure were political,” he says. “It was not operational or efficient.”

For example he points out that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration should never have been put in the Commerce Department. “People who are appointed commerce secretary are typically trade people,” Reilly says. “They’re not environmental or scientific people. NOAA is only part of the Commerce Department because the Interior secretary in the Nixon administration attacked the Vietnam War policy — so no way was Nixon going to give a large, new agency to the Interior Department, which is where it had been slated to go.”

Reilly’s point is that in a future reconfiguration, these issues can be fixed. “We can put NOAA, Fish and Wildlife, and the Interior exactly where they belong in a newly structured EPA,” he suggests. “Maybe it won’t be the EPA — make it the Department of the Environment, full cabinet level. That’s where I would place my mind and attention.” Reilly says the EPA Alumni Association created a project team to contemplate how to rebuild the environmental protection and regulatory apparatus.

“The EPA wasn’t perfect,” he says. “We weren’t perfect. We can do better, and we have to. We can rebuild the EPA. I don’t know if I will be around to be part of it, but I believe it will come sooner than we think. If we don’t have a functional FEMA, if people go to our national parks and discover there are not sufficient rangers to manage the waste and crowds and take care of the trails, the country might become very impatient.”