Has the following ever happened to you? One of your co-workers got the promotion you wanted, even though their professional credentials and achievements at work were not as good as yours. Unfair? Perhaps. But maybe it was simply because your colleague was better at “selling” their achievements than you.

As an entrepreneur, I have noticed time and again that there are two types of people: There are employees who quietly and modestly go about their work, but whose performance (unfortunately!!) doesn’t gain the recognition it deserves because their boss doesn’t even notice what they really do. Then there are others who have learned a lesson from chickens! Yes, you read that correctly. Chickens cluck every time they lay an egg. And that is exactly what you should learn to do.

And what is true for employees is even more so for the self-employed and for entrepreneurs – both small and large. At a time when we are flooded with information through the media and online, it is less important than ever before to simply be good at something. Anyone who believes that “quality will prevail on its own,” “the cream will always rise to the top,” or “you shouldn’t blow your own trumpet” will have to accept it as they are passed over for promotion by colleagues who know how to build “the brand me.”

“You can have the greatest movie in the world, but if you don’t get it out there, if people don’t know about it, you have nothing. It’s the same with poetry, with painting, with writing, with inventions!” These are the words of Arnold Schwarzenegger, who, at the beginning of his career, took a stroll through downtown Munich wearing nothing more than a skimpy pair of posing briefs. He had asked a friend to call some journalists: “You remember Schwarzenegger who won the stone-lifting contest? Well, now he’s Mr. Universe, and he’s at Stachus Square in his underwear.” The next day he was in the newspapers. Schwarzenegger is one of the most famous people in the world. He owes his unusual career – as a bodybuilder, Hollywood star, politician and entrepreneur – to his sales talent. There have been many bodybuilders since with bigger muscles than Schwarzenegger, but none of them were so good at selling. That’s why you don’t know their names, but you know his.

Some people believe it is enough to be “good” at something because quality will eventually prevail on its own. That is naive. If that were the case, companies such as Mercedes or Apple could have stopped their advertising and PR campaigns decades ago.

Even people we don’t normally associate with self-marketing owe much of their fame to their ability to build their personal brand, even those who claim that fame is a nuisance to them. Even Albert Einstein, the most popular scientist in history, asked himself in one of his famous verses whether it was he or his admirers who were really “crazy”:

“Wherever I go and wherever I stay,

There’s always a picture of me on display,

On top of the desk, or out in the hall,

Tied around a neck, or hung on a wall.

Women and men, they play a strange game,

Asking, beseeching: ‘Please sign your name.’

From the erudite fellow they brook not a quibble

But firmly insist on a piece of his scribble.

Sometimes, surrounded by all this good cheer,

I’m puzzled by some of the things that I hear,

And wonder, for a moment, my mind not hazy,

If I and not they could really be crazy?”

But no one becomes truly famous by chance or against their will, at least not over years and decades. In my book How People Become Famous, I take the examples of twelve famous figures to show that, although they all complained from time to time about the annoying side effects of fame, they also all consciously strove for it and spent a lot of time and energy on self-promotion.

Take Einstein again: The photo of him sticking his tongue out at the world became famous. It was taken on his 72nd birthday and shows his successful transformation from man to metaphor. Einstein himself chose a detail from the photo, had the image cropped, printed and sent to friends and colleagues. The image became his ultimate trademark and a pop motif for posters, buttons and T-shirts.

Einstein cultivated the image of the scientist who attached little importance to clothing, hated collars and ties, did not comb his long hair, wore no socks and left his shirts open. Asked about his profession, he once quipped, “Fashion model.” Rumor has it that as soon as photographers approached, Einstein mussed up his hair with both hands to restore his quintessential image as an eccentric professor.

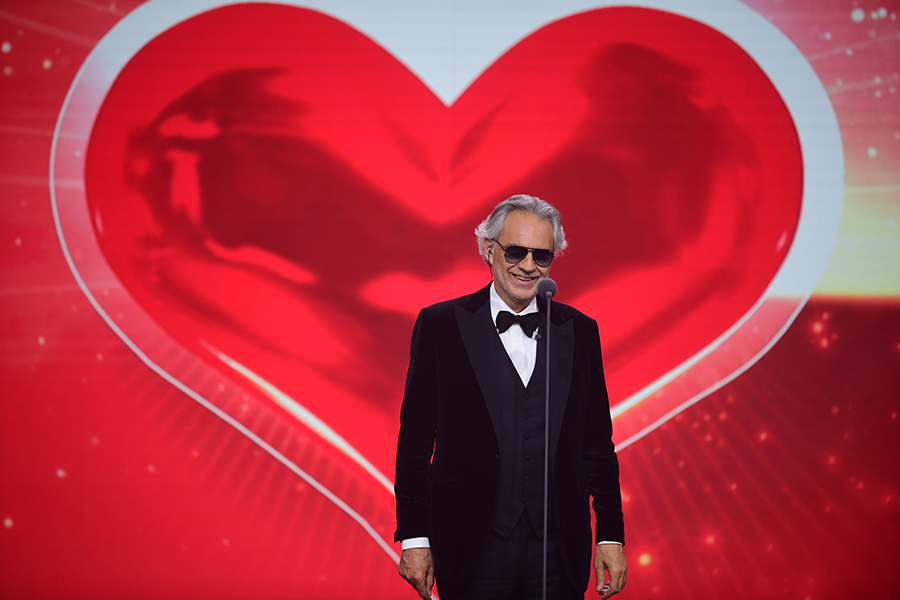

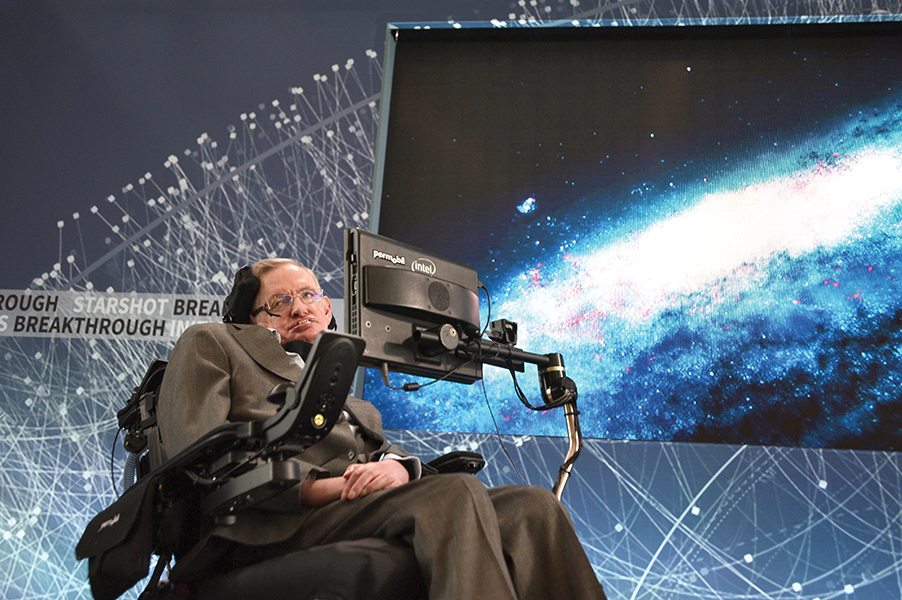

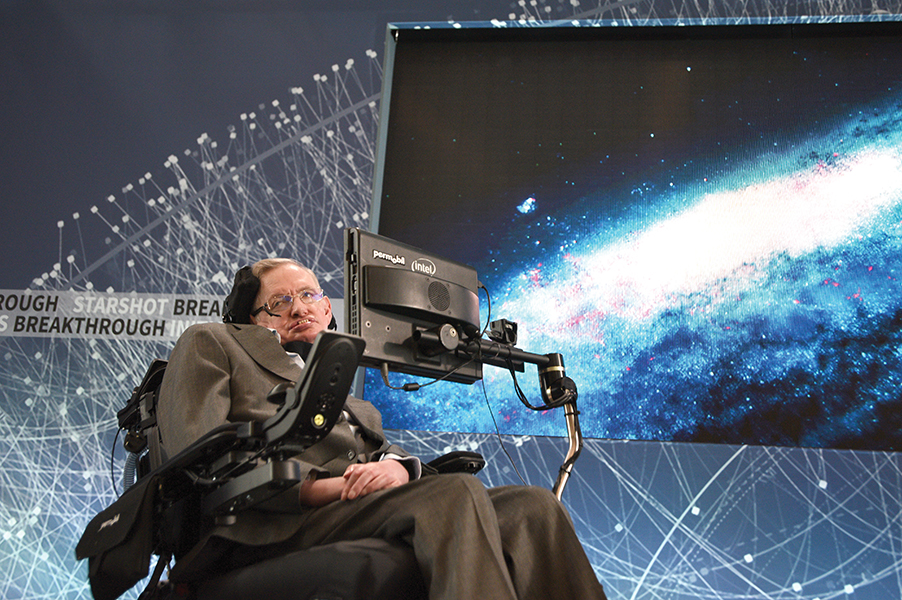

Einstein certainly didn’t become famous for the theory of relativity, because 99.99 percent of the people who cheered him whenever he appeared in public didn’t understand it. Then there’s Stephen Hawking, who became the most famous scientist of recent decades, despite the fact that he never won the Nobel Prize. He once confessed: “To my colleagues, I’m just another physicist, but to the wider public I became possibly the best-known scientist in the world.” He understood the art of self-promotion like no other scientist since Einstein. Hawking – unlike most other scientists – was not prepared to settle for a life writing technical essays that would only ever be interesting and comprehensible to his scientific peers or giving lectures at specialist conferences.

When negotiating with publishers, he demanded that his next book should be available in airport bookstores all across America: “If I was going to spend the time and effort to write a book, I wanted it to get to as many people as possible.” That in itself is an unusual attitude for a theoretical physicist. In fact, his book A Brief History of Time spent 147 weeks on The New York Times bestseller list and a new record 237 weeks on the London Times bestseller list. It has been translated into forty languages and sold ten million copies. How many people ever fully understood the book is another question.

Hawking, with great self-awareness, once explained: “Undoubtedly, the human interest story of how I have managed to be a theoretical physicist despite my disability has helped.” A marketing genius, he built himself into a brand, turning the disadvantage of his disability into a distinctive brand feature. He even patented the computerised voice he used to communicate.

You don’t have to aim to become as famous as Einstein, Hawking or Schwarzenegger. But you can certainly learn a lot from them. Above all, this: It’s not enough to be good. You also have to make sure that others take notice. Do something good – and talk about it!