After the many sessions in Glasgow at the United Nations COP26 during October and November, the promises made and actions foretold, plans must turn into policy and action. The looming challenge exists of mobilizing capital to fund climate-related infrastructure now and in the future.

To finance the low-carbon energy transition to adapt to climate change risks, the International Energy Agency and other global watchdogs project that massive amounts of capital will be required. The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, formed pre-COP26, estimates that $125 trillion will be needed to close the 1.5- degree scenario gap to the year 2050, also known as net zero. Specifically, from 2021 to 2025, $2.5 trillion is needed annually and $4.5 trillion from 2026 to 2050, over four times more than that of today. [i]

At the COP26, the Glasgow Alliance, financiers with assets of $130 trillion under their purview, plan to transition their portfolios to net zero by 2050, an enormous undertaking.[ii] Some large players have admitted they are not sure how to get there. That’s the honest truth. In their roadmap scenario of the opportunity set in climate-related and sustainability financing the idea of blended finance is posed for infrastructure projects that are typically financed by the public sector; blended finance, they suggest uses public monies to leverage private sector capital and is highly suited to developing country needs where the risk profile is higher. In terms of infrastructure funds, the Alliance estimates $972 billion is the amount needed or potential they could support to reach net zero goals, much of it focused on electricity infrastructure.[iii] Developing countries still need all other forms of infrastructure for water, waste, transportation and the like. Many of the net-zero roadmaps are more geared to industry sectors touching the low-carbon energy space.

Off the sidelines

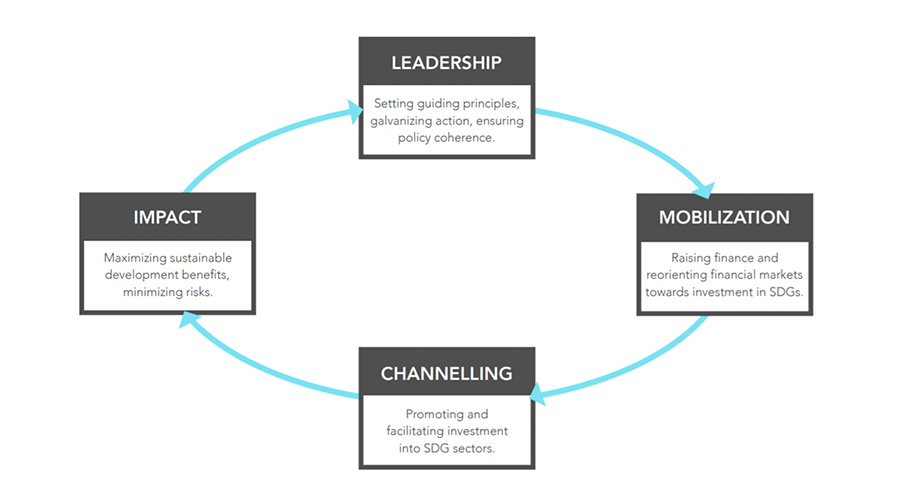

The outsized amounts of capital requirements being put forth begs the question: Who will pay for this global low-carbon campaign and the interconnected sustainable development goals? The Glasgow Alliance believes 70% of the funding for net zero can come from the private sector. While many types of financiers have obvious roles to play in theory, in practice we need an approach that will motivate and incentivize private capital to come off of the bench.

One approach which captures the need for a shared financing approach is through capital markets-based public-private partnerships (PPPs). Simply put, since large sums of capital will be required, a project(s) approach based on the financial feasibility that capital market discipline would bring offers a path forward. We cannot afford to waste resources and time. The urgency communicated by scientists about the need to reduce emissions sooner than later means that financing such an energy transition has to be efficient, matching capital and timings optimally.

Global capital markets offer a viable source of diverse funds, promote better governance, and can bring efficiency and transparency to the infrastructure financing challenge. The experiences to date with privatizations and securitizations suggest that a “market finance” approach versus traditional PPPs with “contract finance,” can create immediate private ownership of public-investment projects among diverse groups of investors. It can ultimately lead to more efficient and successful infrastructure development. Market-based financing solutions can help bring more rational economic decision making to infrastructure projects and the “real” economy. Projects should be founded on cost-benefit analysis for which public and private sector actors have an important oversight role.

A role for markets

The financing of projects should be guided by global capital markets’ invisible hand to determine the economic value of an infrastructure project and provide the necessary resources for construction, operations, and maintenance. In this truer form of public-private partnership, government focuses on identifying and facilitating the project and then allows the private sector to create an efficient, sustainable public-works asset that offers a financial reward to risk-takers and its owners. When contractors and the trades lead project development, as with typical public sector-led infrastructure projects versus investors, their incentives often override performance and cost efficiency.

Recent research has shown that public institutional investors in infrastructure that are Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) signatories underperform private infrastructure investors. This rests partly on the fact that they invest in marginal deals.[iv] For any new large-scale infrastructure project, securitizations specific to the project or initial public offerings of project securities can be designed with financial innovations. This would create diversification, liquidity, and mitigate many of the problems that accompany existing approaches in financing infrastructure. Importantly, it would foster transparency.

Financial innovations in the securities offering can serve as both a deterrent and an incentive. For example, including event-risk provisions in project bonds can deter politicians’ attempts to make undesirable policy changes, fostering a more investment-friendly environment that developing countries often seek. Proper transparent management will bring its own reward through enhanced project value for the community and economy at large. In the end, the explicit costs of debt financing for infrastructure would be lower. Of great consequence, the invisible hand of capital markets may prove more capable in setting infrastructure project agendas which span varied administrations and political agendas.

This approach would bring true public-private sector participation in sustainable development goals. It would ensure ample funding, strong interest, and awareness of a project on a global scale. Managerial incentives could be more aligned with productivity, thus reducing the widespread problems of cost overruns and inefficiency. Government—at central, state, and local levels—could be allocated project securities to achieve real public-private ownership.

Market-based PPPs can address investor reluctance due to political risk and profitability concerns, bring projects online more quickly, and attract long-term institutional investors. This financing approach can be applied to groups or consortia of new smaller-scale projects as well. An IPO that includes an entire value chain from production to final consumer in the carbon capture space is an example. A sustainable complex of energy-related projects focused on renewable biofuels is a possibility, or a large-scale energy system specific to a geography or special situation would be a candidate.

The transformational sustainable mission suggested by net-zero commitments of various global stakeholders, needs a novel approach, based on existing financial market structures. To rise to this 21st century decarbonization challenge, a market-based public-private partnership has the capacity to complement sustainable development with sustainable finance.

Dr. Andrew Chen is Distinguished Finance Professor Emeritus, Cox School of Business, Southern Methodist University and Jennifer Warren is principal of Concept Elemental, a sustainable resources consultancy and energy writer.

[i] https://www.gfanzero.com/netzerofinancing/

[ii] https://www.wsj.com/articles/financial-system-makes-big-promises-on-climate-change-at-cop26-summit-11635897675

[iii] https://www.gfanzero.com/netzerofinancing/

[iv] https://www.unpri.org/pri-blog/the-underperformance-of-public-institutional-investors-in-infrastructure/8625.article