So you want to save money in your business? Where would you start? Most companies will begin looking at staff or existing suppliers when cutting costs. But what about waste?

According to Rick Perez, Chairman and CEO of Houston-based Avangard Innovative (pictured above), there’s profit to be found in your factory waste bins. To prove it, some of his clients have reported returns of twelve times the savings on their waste. “You’ve already paid for the packaging on items you’ve bought,” says Perez, “so you’ll get 100 percent profit if you turn this waste into a commodity; something useful.” Rather than paying someone to cart trash away, Avangard has pioneered an ingenious business model that reverses the value chain, turning trash into an important budgetary item.

“We turn waste into money, something most companies don’t focus on,” says Perez. “It’s amazing what’s thrown into trash bins that companies are unaware of. We get skeptical glances at first, but once we’ve tracked it and presented a report, it’s much easier to show a dollar value to clients. Then they’re happy to pocket the cash.”

Perezs’ story is the classic American Dream. Arriving in the U.S. from Mexico City at an early age, he worked his way through school and university, always believing that new opportunities lay around the next corner. His father, a serial entrepreneur, had instilled a work ethic in Perez that taught him that hard work pays. His early career included a stint as a waiter and packing supermarket bags – work experience that any successful entrepreneur will only value later in life.

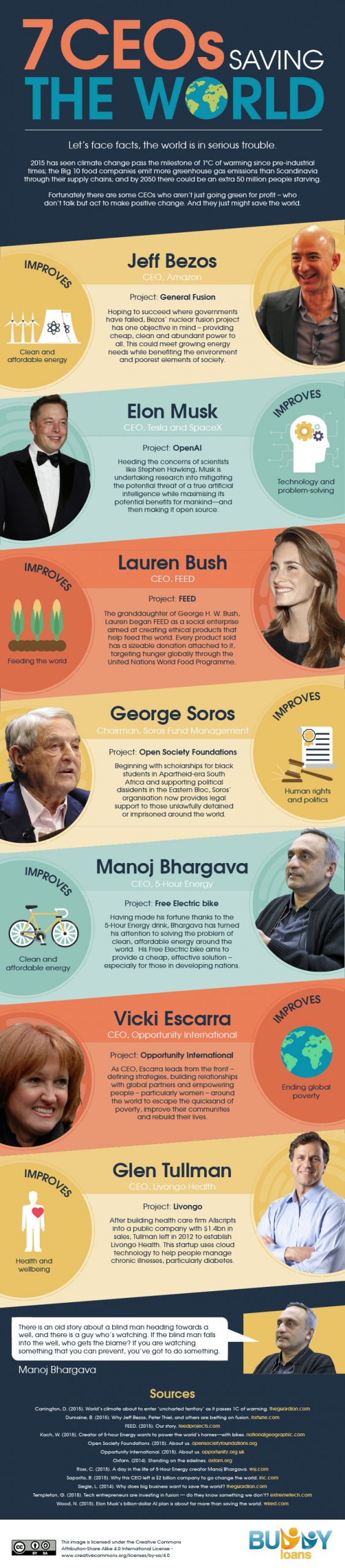

His ‘aha’ moment came when his brother, who worked at Merrill Lynch, told him about the deposit paid on returned Coca-Cola and Pepsi bottles. It had been an effective recycling system since being introduced in the U.S. in 1972, but Perez was one step ahead and had seen the future – discarded ‘one-way’ plastic bottles that would soon start flooding landfills. A fortunate trend at the time was an increase in the demand for synthetic fibers, used in the manufacture of polyester-based products. Avangard was soon processing 94,000 tons of plastic bottles and became the largest recycler of plastic bottles in the world.

Perez next swung his attention to supermarket chains, retailers and grocery stores, all with similar dilemmas around their waste packaging. Avangard developed a tech system that captured the data of recyclable material in real time. If you think Silicon Valley has an edge on innovation with their cool tech gadgets, think again. Perez has created the world’s first ‘trash-tech’ company.

So, how exactly do you convince a CEO to take their trash seriously? Perez reckons that once management moves beyond legislation and compliance issues and realizes they can make shareholders happy by increasing profit, the barriers disappear.

“Most annual reports have a page on sustainability nowadays. This offers a new opportunity for CEOs to shine,” says Perez.

The numbers don’t lie. A typical grocery store chain can achieve 20 percent of their net profit through waste recycling and improved efficiencies. “We’re mostly dealing with customers who already have a trash and recycling program in place, but we’ve redesigned the system to create profit,” says Perez. Most companies throw people at their trash problem, Avangard throws technology at it.

The cost of start-up equipment is minimal and the globally active company supplies all maintenance and training. Most customers will see a return on their investment within 12-18 months. Charlie Chanaratsopon, CEO of Charming Charlie Inc., was skeptical at first, but has now seen the benefits. “Avangard has allowed us to understand the composition of our waste, and therefore the value,” he says. “It’s brought an entirely new level of discipline to our sustainability program and by outsourcing this to Avangard, we can focus on what we do best: run our business.”

Finding value in your trash is great for generating profit, but Perez has always had his eye on a grander cause: helping save the planet. “Anything we can do that takes away from dumping things into landfills and acknowledges the importance of the environment, is a good goal,” he says. Most companies view sustainability programs as a cost, but Perez sees exactly the opposite – an opportunity to make money. “You’re also cleaning up cities and towns – there’s a social dimension as well,” he says.

Hosting events with quirky names, such as Styrofoam Amnesty Day, has helped Avangard raise awareness around the recycling of ‘difficult’ substances, while demonstrating they can indeed be recycled.

Waste is everywhere in a supply chain: cartons, pallets, buckets, tubs, lids, drums, used oil and organics. Many CEOs already know there’s a cost associated with getting rid of these items as they’ve paid for trucks to remove them, yet very few see waste as an asset – that someone owes you money on.

Recycling is not new either and Perez is aware that many view his sector as low-tech. His advantage lies with technology and tracking – a system that generates detailed reports through a control center that will inform CEOs on the status of a factory product, even before their own internal stock systems can. “When you have the right data, you can execute a plan,” says Perez.

It also helps that our software can generate sustainability numbers to use for marketing purposes – an important factor when positioning your brand with consumers who want to see a commitment to social impact before buying. “Think of us as your instant sustainability campaign,” laughs Perez.

Larry Del Papa, President of Del Papa Distributing, was surprised by the sheer volume of their waste. “We can now track our recyclables to maximize our revenue with Avangard, just like our other products,” he says. “We’ve increased our recycling revenue, cut our trash bill, helped the environment and boosted our bottom line.”

“Every company tracks their products, yet somehow waste and recyclables aren’t,” says Perez. “The receiving depot at the back of your store should be viewed as another money-making opportunity, on-par with the front-end, where consumers buy your products. Once you’ve convinced employees and your board that trash is a valuable commodity that is being given away, or even stolen, it will get treated differently.”

Perez feels the new generation of young people will usher in a new era of recycling, and with it bigger business opportunities.

“The kid’s of today know about recycling,” says Perez. “They know it’s the right thing to do, and a company that adopts a culture of recycling today will benefit from future generations (the future CEOs and employees of the world) who will understand that trash can be a normal part of any business plan.”

“We should all aim to leave something valuable behind for the future,” says Perez. “I’d like people to look back on my legacy one day and know that I turned trash into a valuable commodity.”