The failed 2019 UN Climate Conference in Madrid ended in mid-December just about when the massive wildfire destruction of Australia’s bushlands was beginning.

The wildfires that broke shortly afterward took the form of a Gaia-like revenge. Australia, along with the United States, Japan and Brazil, had been among the countries that had blocked real progress at the UN Conference of Parties (COP25) on a more realistic system of carbon emissions accountancy – that could track and ensure real progress on emissions reductions over the critical coming decade.

And the price exacted was almost immediate – in terms of ecosystems and wildlife damaged, and ultimately human health and well-being.

The converging problems of global warming, environmental degradation, and public health have been well-reflected in the bushfire destruction, along with a record drought in southern Africa, floods elsewhere, and off-the charts air pollution in Delhi, India, all occuring just as 2019 ended and the new decade of 2020 began. And therefore it is not surprising that climate has been placed at the top of the 2020 agenda by groups as diverse as the World Economic Forum (WEF), as well as the World Health Organization.

The Global Risks 2020 Report, released last week, just ahead the WEF meeting that begins Tuesday in Davos (21-24 January), notes “climate response shortcomings” as well as “biodiversity loss impacts” among the top two out of five categories of risks faced by the world for 2020. “Creaking health systems” is listed as a sixth.

WHO has also listed the climate and health crisis as among the 13 top threats to global health in the next decade. Among the other threats highlighted by the agency – as well as by a range of experts interviewed by Health Policy Watch about the globala health outlook for 2020, include:

- Emergence of new diseases at an increasing rate and intensity – as reflected in the Wuhan pneumonia outbreak;

- Stalled action on medicines price tranparency – watch to see if European countries take a lead this year in adopting stronger measures;

- Failing medicines markets contributing to the rise of anti-microbial resistance (AMR) – when prices for other vital drugs, particularly antibiotics, dip too low;

- Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) and Universal Health Coverage – how the global “syndemic” of obesity, undernutrition and climate change creates barriers to achieving UHC.

Digital health and AI technologies – which hold much promise for improving health, but also create new ethical challenges – were among the other issues cited by experts interviewed by Health Policy Watch. Long-simmering neglected diseases, often pushed to the sidelines of health agendas was another issue noted, as the world prepares to observe on 31 January, the first-ever World NTD Day.

The global shortfall of health workers, as well as gender challenges faced by women who dominate the lowest ranks of healthcare professionals, is another issue that will be highlighted prominently this year, which WHO member states have designated as “The Year of the Nurse and Midwife.”

Climate and Health

The real-world convergence of climate and health agendas has been playing out in the Australia story, which has left some 29 people dead, uncounted numbers of people displaced, and over 1 billion animals killed – driving some species to the brink of extinction. There has been a 30% increase in asthma cases and more children presenting with respiratory infections, Sydney doctors have reported. Scientists, meanwhile, have said that the long-term human health impacts of exposures to the air pollutants “won’t be known for years.”

But immediate health impacts were visibly demonstrated to global audiences during the initial, pre-qualifying rounds of the Australia Open, where the Slovenian Dalila Jakupović collapsed on the tennis court choking for air, and other stars also cancelled matches underway. Canadian Liam Brody later tweeted that players’ blood was “boiling” over the decision to continue the games in such hazardous air quality conditions.

Ironically, just four weeks earlier, as the December COP25 climate talks wound up, it was Indians in Delhi who were gasping for breath, and Australia was among the handful of countries to thwart a critical deal on how to count countries’ carbon reductions, in order to meet the pledges of the 2030 Paris Climate Agreement.

Along with Brazil and the United States, the conservative government of Prime Minister Scott Morrison, insisted on using carryover credits from the expiring 1992 Kyoto protocol, a loophole criticized by Costa Rica, New Zealand, France as something that would thwart accurate measurement of real progress, and even described as “cheating” by former French minister Laurence Tubiana, an architect of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The Australia narrative illustrates the Global Risks Report finding that “climate response shortcomings” are among the top five risks faced in 2020. “Weak international agreements belie rising investor and popular pressure for action, against a multitude of natural catastrophes and indicators of longer-term disruptions,” the report states. “2020 is a critical year for nations to accelerate progress towards major emissions reductions and boosting adaptation actions.”

Experts have described Australia’s experience as just a taste of what to expect in the world’s most fire-prone continent from a changing climate. The year 2019 was the hottest year for the country on record, with average temperatures 1.5C° higher. Rising temperatures and lower levels of winter rainfall dried out bush and forest cover, which more readily become fuel for summer fires, occurring with greater frequency in the prolonged heat and drought conditions.

In just three months, Australia’s fires are estimated to have released 350 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, said climate experts quoted by the Sydney Morning Herald, warning that a century or more will be needed to absorb the carbon dioxide released. Drifting smoke from the fires has by now lapped around the world, and turned glaciers in nearby New Zealand brown – darker glaciers accelerate ice melt, in turn threatening the long-term stability of water reserves.

It’s also a record year for drought in Southern Africa with 12 countries affected, including Zimbabwe, Angola, Eswatini, Mozambique, and South Africa. The World Food Programme estimates a record 45 million people in Southern Africa are food insecure, including 5.1 million in Zimbabwe. That face of climate change may have had even more dire, immediate, human health consequences. But there is no Australia Open playing in Harrare.

Climate & Health Lack Synergies

Within the broader spectrum of government failure, health and climate sectors remain disconnected – sapping efforts to face a common threat to human health and well-being.

“The climate community lacks both the political leverage, the experience and the institutional mechanisms of the health sector—this expertise is badly needed for climate negotiations, but we don’t really work together,” lamented one senior European negotiator to Health Policy Watch, during the Madrid COP25.

He contrasted the high-profile October Global Fund Replenishment event in Lyon that had raised $US 14 billion to combat just three diseases, HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria, against the Green Climate Fund Replenishment conference that took place in Paris two weeks later. The latter raised less than US$10 billion for four years – and that was far short of the $US 100 billion in near-term climate finance that developed economies had pledged to channel to developing countries at the 2015 Paris Climate Conference.

“If you look at the Global Fund Replenishment, Emmanuel Macron, Bill Gates as well as Bono were all there,” lamented the negotiator. “But who even heard about the Green Climate Fund event? Was there a Gates or a Macron or a celebrity like Bono? No.”

In fact, behind the rhetoric, there are few formal institutional mechanisms to bring the knowledge, capacity and power of the health sector to bear on climate negotiations or to inform effective climate policies, at either national or global levels, he remarked.

One obvious reflection of that is the fact that year after year, attendees of the COP climate meetings include virtually no health ministers – with the exception of delegations that have been sponsored by WHO from time to time, from groups such as Small Island States, are faced with the virtual disappearance of their nations as a result of climate change.

This year, while climate delegates were huddling in Madrid in December, major health conferences were also going on in Brussels and in Oman, around non-communicable diseases. Meanwhile, WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Gheyebresus was in Geneva putting the final touches on an organizational restructuring plan. WHO’s Maria Neira, who has won acclaim as the WHO’s lead on climate, health and environment, was pulled back to Geneva by the WHO Director General before the conference ended.

“With the exception of the Gender Action Plan, agreed by the end of the meetings, discussions did not bring to agreements and ended up in a disillusioned domain of unmet expectations,” reported Flavia Bustreo, chair of governance for the Interagency Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, one of the few health officials to attend Madrid’s COP25.

She added that: “A low number of debates concerning the link between climate change and health suggests a low prioritization of what is now one of the biggest issues in this ongoing crisis.”

Grassroots Activists Target Finance & Fossil Fuel Producers

Outside the halls of debate, however, youthful protestors have been ramping up their campaigns against governments, fossil fuel producers, as well as their industrial and financial partners. Here too, Australia’s government has been a recent target, and tennis has even played a role.

Late last year, the Australian government approved the long delayed opening of the Carmichael open pit coal mine, the world’s largest, to supply fuel to India – just weeks before the bush fire emergency. The 447 square kilometre project owned by the Indian company Adani, has been hotly criticized by Australian environmentalists as a threat to the Great Barrier Reef.

Then in January, climate activists, including Sweden’s Greta Thunberg, called on the German engineering group Siemens to withdraw from the project; Siemens is to supply rail technology to transport coal from the mine. On Monday (January 13), Siemens rebuffed those calls.

Another prominent target has been Credit Suisse. In mid-December, in fact, the bank announced that it would stop lending for new coal-fired power plants, following on its decision to halt lending for new coal mine development. But the bank remains one of the world’s largest investors in fossil fuel companies with a US $57 billion portfolio, critics say. Swiss climate activists have called upon the bank, as well as its ambassador the billionaire tennis star Roger Federer, calling on them both to step back from fossil fuels.

Last Friday, Thunberg joined Swiss activists at a climate protest in Lausanne, at the end of a week where protestors ramped up a @RogerWakeUpNow campaign aimed at Credit Suisse and Federer, who is also competing in the Australian Open.

That followed a landmark Swiss ruling on Monday (13 January), where young activists associated with Lausanne Action Climat were acquitted by a local court of CHF 21,600 in fines for storming a Credit Suisse office in 2018 with tennis rackets and balls. In an unprecedented decision, the judge declared that the urgency of climate action in the public interest outweighed their violations of the law.

A day later the protestors entered the Swiss offices of UBS, another major investor in fossil fuels, and dropped bags of coal on the floor.

“So far during this decade, we have seen no signs whatsoever that real climate action is coming and that has to change. To the world leaders and those in power I would like to say, that you haven’t seen anything yet, you have not seen the last of us. We can assure you that,” Thunberg told cheering crowds in Lausanne on Friday.

Such scenes may become more common throughout 2020 as youth activism, fueled by public concern over climate grows, while governments and industries try to carry on business as usual with fossil fuels. As the next stop, Thunberg and other climate activists are heading to the WEF in Davos, to demand that financial leaders halt investments in fossil fuels.

“We don’t want these things done by 2050, 2030 or even 2021. We want this done now – as inright now,” Thunberg said in a Guardian Op-Ed published Monday (20 January) with other youth climate activists. Since the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, 33 leading banks have poured some $1.9 trillion into fossil fuels, the op-ed noted, and an International Monetary Fund report estimates that in 2017, the world spent $US 5.7 trillion in fossil fuel subsidies.

Although oil-producing Abu Dhabi rang in 2020 with a Futures Energy Summit devoted to clean energy, in fact investments in renewables in developing countries “plummeted” in 2018, according to a November 2019 MIT Technology Review. Coal power production in 2018 reached an all-time high according the International Energy Agency. And across southeast Asia as well as parts of Southern Africa and the Middle East new coal power plant development continues apace, much of it driven by Chinese and Japanese investment.

Natural gas is also having a heydey. While less damaging than coal, natural gas development has often been at the expense of even cleaner solar energy sources, critics say. In the sun-drenched Mediterranean region, Turkey celebrated the New Year with the launch of a new natural gas pipeline connection to Russia; Israel launched its second major natural gas platform; and regional tensions heightened over conflicting claims between Turkey and Libya on the one hand, and Greece and Cyprus, on the other, to other potential Mediterranean gas reserves – creating new and dangerous sources of regional political tension.

What To Watch in 2020

The 2020 Climate Conference in Glasgow on 9-19 November (COP26) will confront all of these financial and political forces head-on. This is when countries will gather to make new political commitments on emissions reductions. The European Union’s landmark agreement to reach net zero emissions by 2050, formally announced on 13 December, represented one important bright spot in the otherwise dim closing hours of the Madrid COP. Significantly, that commitment was also accompanied by a €100 billion pledge in funding by the European Commission to help the ease the energy transition, particularly among some of the region’s most coal-dependent countries, such as Poland, as part of a European Green Deal Investment Plan that aims to attract €1 trillion in public and private finance over the next decade.

But the last hope for the global community to prevent temperatures from rising above 1.5°C still appears dim – if fossil fuel development across the rest of the world moves forward unabated, and the United States, which has announced that it will withdraw from the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, follows through on that promise right after the US Presidential elections. Those elections are scheduled for 3 November, just days before the Glasgow COP26 commences.

Whether European leaders can and will wield sufficient muscle to convince the other big drivers of climate change to change course, including both high-income Australia, Japan and the US, as well as emerging economies led by the “BRICS” of Brazil, Russian, China and South Africa, remains an open question. Not only will COP26 be the year’s climax in climate policy-making – it could be the most decisive meeting for decades to come.

Leading up to that, observers can expect to see more youth-driven protests around Europe and elsewhere, and more civil disobedience. It remains to be seen if this will capture the imagination of the broad public – or exacerbate social confrontations with other interests, such as public opposition to higher fossil fuel prices. It was, after all, Emmanuel Macron’s earlier moves to raise fuel prices, which triggered the prolonged, and often violent, “Gilet Jaune” (Yellow Vest) protests seen in France over the winter of 2019, as well as civil disturbances in Africa and the Middle East on other occasions.

Also expect to see a series of protracted technical negotiations between countries over the new 2020 commitments to protect the world’s biodversity. Biodiveristy underpins what scientists call critical “ecosystem services” to health, such as food and fresh water supplies, sources of existing and future medicinal plants, as well as certain forms of natural regulation of infectious diseases.

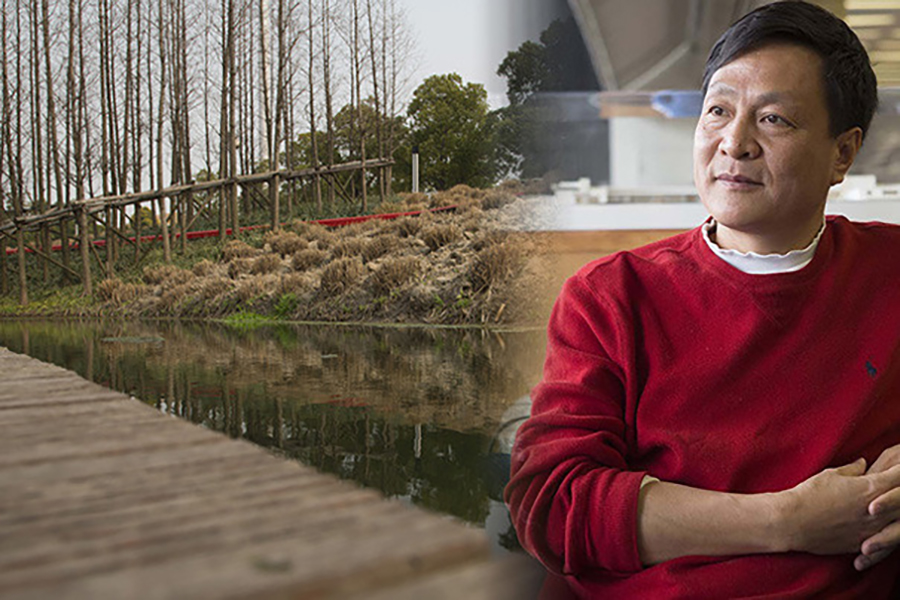

At February meeting of the UN Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) in Kunming, China, technical experts will wrangle over proposed new targets for protecting the world’s seas, open spaces and species, hopefully paving the way for a new global agreement at the 15thCBD Conference of Parties in October. The agreement aims to halt the increasingly rapid decline and extinction of plant and animal species – after the 2010 CBD targets were largely missed.

Biodiversity loss is another topic on the Davos agenda, having been included among the top five risks in the Global Risks 2020 Report. The ways in which biodiversity loss threatens the stability of future food supplies and medicines discoveries, as well as other life support systems, are laid out in a WEF blog by a top official at Zurich Insurance Group – illustrating how an longtime scientific concern is now drawing attention from actors such as the insurance industry.

As for measuring progress on bringing health and climate agendas just a little bit closer together, watch out for where WHO’s top leadership will be in that critical week of November 9-19 – and what ministers of health, as well as rank and file doctors and nurses are saying and doing during Glasgow’s Climate Conference.

By Elaine Ruth Fletcher. This story originally appeared in Health Policy Watch and is republished here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration to strengthen coverage of the climate story.