What if Pascal was right when he said, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” If I am honest with myself, I can see that I live mostly in perpetual busyness and distraction. I don’t often pause for long enough to notice what needs improvement in my life. Course correction requires a real pause. We can not change the wheels to the car while still driving it.

Ask yourself, what is your threshold for being alone with yourself? Being witness to the inevitable fear that emerges beyond the boredom. Can we pause long enough to face our problems, those things that we can see so clearly magnified in the conditions of the world?

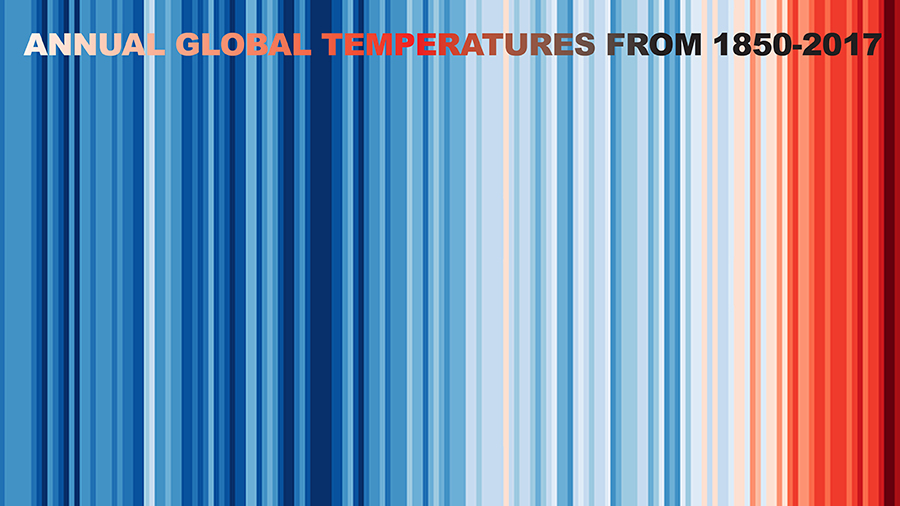

Many of us say we want to get back to business as usual, but let’s pause for a moment and investigate “business as usual.” A perpetual growth economy that continues to degenerate the life and biodiversity of our planet, “feeding the world” by destroying our soils, powering our grids while exacerbating global warming, expanding digital communications only to expose ourselves to increasing levels of electromagnetic radiation, prescribing a drug for almost everything while very few are genuinely well.

Business, as usual, has led to the world’s richest 1% having more than twice as much wealth as 6.9 billion people combined while 9 million people die annually of starvation.

As far as I can tell, business as usual will take us into the 6th mass extinction. And although many of us are all racing to solve the world’s problems, something in our approach is off.

In this time of mandatory quarantine, perhaps we are being given a gift of pause and retrospection that may have only otherwise come to us on our deathbeds. We are all being invited to look at ourselves and ask, is this the way of life I want to pass on to my children? Is this the life that fulfills my heart?

Is there a possibility of a new normal?

We have culturally created time to pause (weekends & holidays). Time to be still, connect with ourselves, our loved ones, and give thanks for the bounty of the Earth. Time we can utilize to re-align ourselves to our higher purpose and make course corrections to our lives and see where we may have been missing the mark. Unfortunately, these pauses haven’t been enough for us to change the trajectory we are on.

When we ignore the whispers, the communications get louder until they become a scream. STOP! Is this what we are being told directly and indirectly?

The reality is that we have become disconnected from ourselves and our ecology. We are part of Nature, and Nature is always self-healing, balancing, and regenerating. Can we see this virus as part of Nature asking us to slow down, and to live with more reciprocity, care, and reverence for our mother earth who gives us everything?

There is a misconception that our relationship with Nature is inherently destructive.

This is a myth that has been perpetuated for so long that it’s difficult to shift our view. Yet many indigenous cultures have known and lived in a relationship of reciprocity with the living Earth. Seeing themselves as an intricate part of the ecology, living in balance between giving and receiving.

“Action on behalf of life transforms. Because the relationship between self and the world is reciprocal, it is not a question of first getting enlightened or saved and then acting. As we work to heal the Earth, the Earth heals us.” – Robin Kimmerer (Professor of Biology and Indigenous Wisdom Keeper)

Having a symbiotic relationship with the Earth begins with that understanding of connectedness. Not just between people, or more broadly between living organisms, but with the Earth that sustains us all. It’s about going to the literal root of all life — the Earth — and starting there. That holistic approach is best embodied in Regenerative Agriculture. In the simplest of terms, Regenerative Agriculture refers to a method of agriculture that heals and regenerates our land while helping to reverse global warming. The practice sequesters carbon out of the atmosphere and safely stores it in the soil through plants — part of Nature’s naturally balancing technology.

The current systems that produce our food break our soil systems through the saturation of harmful chemicals and a government system that subsidizes farmers to deliver grain to feed animals that we then slaughter to produce meat. This system is unsustainable, and we’re now at the breaking point. In the past 40 years, we have destroyed ⅓ of the world’s agricultural land, pushing our global civilization towards a desertified planet.

For us to survive, this system needs to be dismantled and reversed. Regenerative agriculture is the road map, and everyone who subscribes can participate in global restoration.

Consider the possibility of humans making it their business to regenerate the living systems of the Earth. Time magazine put a price on what it would take to halt climate change through land management and regenerating our soil. Only 300 billion Dollars. This is just 50% of the annual US military budget.

Some business leaders have already taken on supporting regeneration. Ivon Chenard, Founder of Patagonia, declared at Expo West in 2019 that “if your business is not helping to regenerate the earth, start a new business.” They even changed their mission statement to reflect this commitment. “Patagonia is in business to save our home planet.” One of America’s largest food companies, General Mills, just committed to putting one million acres under regenerative management. My organization, Kiss The Ground, is helping to facilitate the farmers in being trained.

Destructive acts of Nature tend to be localized — fires in Australia, hurricanes in the Gulf, a tsunami in Indonesia. This localization allows us to carry on with our lives and not see the connectedness in all beings, and in Nature. And that’s what has been so unique about the pandemic – we see the connectedness of the world. And while the pandemic has taken an incredible toll on human life, global warming promises to extract an even more significant toll.

So the question ultimately becomes: can we act? Can we embrace this great pause and be still enough to listen to our inner voice, the one that will be speaking to us on our last days of life, in regret or gratitude for the choices we made now? Can we begin to see a relationship of reciprocity with mother earth is our only pathway to survival? Human life depends on it.