COVID has proven to be a great lens, showing us the importance of healthcare, education, the importance of care work, and the urgent need to transform our economic values and current systems.

The caring economy is an economic system that promotes the wellness and development of people regardless of sex, class, race, or ability while respecting and taking responsibility for the planet. In essence, the goals of a caring economy align with most democratic constitutions — so do we still search for these values and the superior results they bring?

Is it normal that in today’s world:

- 1 in 3 women experience domestic violence during their lifetime?

- Every year more than 50% of children suffer from violence, and 20% die from that violence?

- More than 700 million people (the majority women) and children live in extreme poverty?

- That, according to the WEF2020 Gender Parity Report, we need 257 years to reach gender equality?

In the past few decades, we have seen a massive increase in deforestation, CO2 production, chemical pollution, and biodiversity destruction. Is this normal? Also, why has conventional economics been so slow to offer compelling solutions to these issues?

Since its theoretical beginnings, capitalism (and even socialism and communism) consider “care work“ — for the young, the elderly, the sick — unnecessary for a “productive” economy, and therefore even today, these at-risk groups are not valued. They continue to effectively be invisible to our culture and the economic metrics of countries and society’s. Consider today’s broad spectrum of politico-economic systems, and ask yourself: do these different systems provide authentic wellness and care for citizens and the environment? The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated our understanding of a harsh reality — that we need to shift to a new economic system that respects all people’s work, and the planet.

So, how did the caring economy begin? The anthropologist Margaret Mead once gave a clear example, when she spoke of a person surviving a broken femur bone thanks to the care of others. Civilization began with the protection and care of individuals. Mead asserted that the act of caring was the first building block of human civilization.

Inspired by four decades of research and activism by Dr. Riane Eisler, Founder and President of The Center for Partnership Studies, we should see the critical pillars of the caring economy as such:

1. To Value and Make Visible Caring for the Environment

As late as 2009, leaders worldwide couldn’t find a way to fight climate change, and the Copenhagen Climate Summit turned out to be an absolute failure. Fast forward six years, and we have finally seen some progress. At the 2015 Paris Climate Summit, many nations, for the first time in our civilization’s history, agreed to pursue collective climate action as the only way to deal with this issue.

Today COVID-19 has shown us that when a public health crisis arises, governments can take quick, sweeping action. So, why have governments worldwide still not taken any real action against climate change? The global pandemic has also shown us that companies that were more environmentally and socially responsible — the ones that cared for their employees and environment — did relatively better. Seeing this accelerated transformation gives us hope — from traditional business values with purely profit-oriented goals, to more sustainable ones that consider all stakeholders.

2. To Value and Make Visible “Care Work”

COVID showed us the importance of healthcare workers, 75% of whom are women. Their pay does not match the dedication and risks they take. In addition, research shows that American women do seven additional years of free care work compared to their male counterparts.

The work of care is invaluable to a functioning society and a necessity that capitalist, socialist, and communist countries take for granted. Many studies show that the Status of Women Predicts the Quality of Life of everybody around them. However, in today’s world, If women are discriminated against in the workplace and their home, and if women do most of the care work for free in their families and work for underpaid wages in the market, a nation’s overall quality of life is negatively affected. Have you considered that our massive economic inequalities exist because currently, we fail to value this care work fully?

3. To Invest in the development of early childhood education: our most important asset

COVID has shown us that all humans, more than ever before, need to collaborate, be resilient, and flexible. To bring those skills to work and home, research shows that the quality of care and education received in the early years of childhood is important . A plethora of other research shows that early childhood experiences directly impact our brain development. Therefore, this will determine later, as adults, how these children will think, feel, act, and even vote. At an early age, children learn what is “normal,” moral, and even inevitable. What is worrisome is that in some cultures, children learn that “one kind of human is more valued than another.” This explains why preserving a rigidly male-dominated, “traditional” family is a priority for authoritarian regimes and religious fundamentalists. Children in these conditions learn another daunting lesson: that to fit into a dominating or hierarchical system they shouldn’t question orders (authority), no matter how unjust. This is one reason why totalitarian regimes survive — because there is tolerance for violence and fear.

4. To Pursue Transparency and Metrics on the Caring Economy: changing our measures of economic health

We measure what we want to grow and improve. The most widely recognized measure of economic health is GDP, created more than one hundred years ago. Mass production and technology have changed since then, and the metrics used to measure success need to adapt to our new reality — one that reflects an authentic measure of the quality of life. One of failures of GDP is that it considers “productive” many activities that do harm, and even take lives: cigarette sales or fast food, as just two examples.

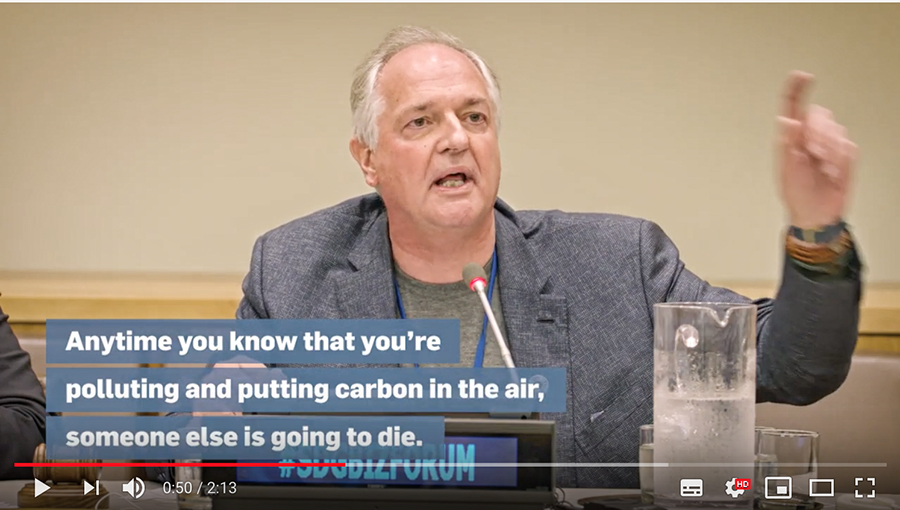

Another example of the failure of GDP metrics is that it doesn’t subtract “externalities,” for example, the cost of natural disasters caused by climate change or a company’s disregard of nature (which might appear as a positive on their balance sheets).

Not only does GDP regard some negatives as positives, but it also fails to include as productive the care work found in households. This, despite studies that show that if it were included, it would represent between 20% – 50% of GDP. Riane Eisler’s Social Wealth Economic Indicators is an excellent alternative for evaluating a nation’s prosperity authentically.

However, none of the suggestions above, that could add to GDP metrics, are taken into consideration by conventional economists and governments. It’s also not taught in schools and universities, so it’s up to likeminded people such as myself and colleagues at Women 4 Solutions to create awareness and action.

COVID has created more gaps between the have-and have-nots worldwide, in addition to some severe environmental problems. Let’s take a look at our current reality: it takes just one infected person to unleash chaos and country-wide shutdowns — the “butterfly effect” of mathematical chaos theory: “that something as small as the flutter of a butterfly’s wing can ultimately cause a typhoon halfway around the world,” becomes a reality.

COVID reinforces the idea that our planet has become a “village,” and technology is still rapidly scaling our interconnected world. It’s now clear that climate action can only be accomplished if all nations collaborate with global goals.

Thus, we have clear proof that we cannot act in isolation any longer. We need a sense of urgency to transform our economic values and systems into something that all humans have had in common from the beginning: caring for each other!

Learn more about the Caring Economy and do something every day to take care of our planet and people!