I never think of shopping as a time for excitement, but in 2019, I was in for a mild shock when I visited my local mall. There, I saw something that only a few years ago would have been unimaginable.

Sears, which took up over a quarter of the mall’s entire floor space, was pulling down its signs. What was once a powerful retail giant is now a glaring symbol of one company’s inability to change and adapt. Sears, however, is not an exception. As we brace for further impact from the global pandemic, more giants are expected to fall. In 2010, in the middle of another crisis, researchers Ranjay Gulati, Nitin Nohria, and Franz Wohlgezogen showed that during the recessions of 1980, 1990, and 2000, 17 percent of the 4,700 public companies they studied did not survive. One out of every three public companies will cease to exist in their current form within the next five years — a rate six times higher than 40 years ago, according to BCG, a global consulting firm.

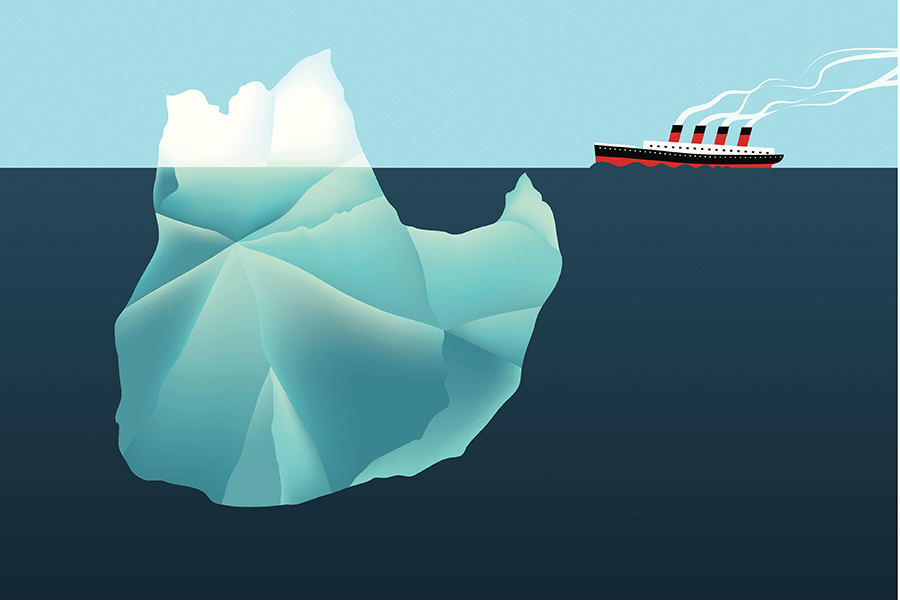

As I stood in the mall and looked at the shadow of what was once a remarkable brand, I was reminded of another story of heartbreaking failure: the Titanic. Titanic’s story offers eerie parallels between the behavior of the ship’s team and that of today’s at-risk companies. Effective leaders know that understanding why things fail can help to avoid repeating mistakes.

Most of us know the story of what happened on that chilly Sunday, April 14, 1912, at 11:49 pm, when the Royal Mail Steamer Titanic — en route from Europe to New York City — collided with an iceberg and sank within three hours, leading to the deaths of 1,514 of the 2,224 passengers and crew on board. The largest moving human-made object at the time, the Titanic was considered unsinkable by all: experts, media, and the public. The ship was equipped with the most advanced naval technology available and a crew of experienced and respected naval leaders. So why did it sink, and what can we learn?

Failure #1 / Ignored Warnings

The Titanic’s crew was warned about the area’s dangerous icebergs. But why were these warnings ignored?

The radio operating team was so concerned with keeping the high-paying customers satisfied that they told the passing ship Californian, “Keep out; Shut up!” when interrupted on-air by his counterpart warning of the upcoming ice field. Customer satisfaction is all the rage. But killing it for the wrong whim of the customer might accidentally kill your business.

Failure #2 / No Binoculars

Overconfidence can be blinding.

The night of the collision was clear and still. Perched 50 feet above the forecastle deck, in a small open box called “the crow’s nest,” lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee worked their two-hour shift. Inside the nest, Fleet and Lee had a large bell to grab public attention and a telephone to reach the captain’s bridge. What they did not have, however, was a pair of binoculars.

A hundred years later, with all the advances in modern technology, it is still hard to imagine any ship in the open waters without binoculars. The Titanic, too, had several binoculars on board, but for much of the trip, they were locked up in a storage cabinet. This was, quite literally, a case of overconfidence that was blinding.

Failure #3 / The Role of the Iceberg

It’s easy to blame the iceberg.

We’ve reviewed some of the causes of the disaster, but we’ve missed the main one: the iceberg. Whenever I work with a company or discuss the Titanic story, the iceberg is the first cause mentioned.

When I’m asked to work with a company to reinvent its products, processes, or business models, I wasn’t there to experience their good times. By the time I’m called, things are already deteriorating — the iceberg has been hit — and oh boy, is it easy to blame the iceberg!

Sneaky competitors, overbearing regulators, lousy weather, bad design, late suppliers, lazy customers, those finance-department knuckleheads: I’ve heard it all. It is so easy to blame it on someone else.

But here is the thing: While you cannot prevent the iceberg from appearing, you can darn well make sure you don’t hit it. The choice is in your hands.

Of all the things that went wrong on the Titanic, there was one problem more glaring than all the others: the arrogance and overconfidence of past successes.

Failure #4 / Previous Success Might Destroy Your Ambitions

What got you here may not get you there.

On the night of the collision, the captain had already gone to bed. First Officer William Murdoch was in charge. At 39, Murdoch had 16 years of maritime experience and was known for his masterful record of averting ship collisions. For instance, before the Titanic, he had served on the Arabic when a passing ship came bearing down from the darkness. Murdock grabbed the wheel and held the ship steady. As a result, the two ships passed within inches without damage.

The Arabic incident was one of many Murdoch mastered in his career. In the 37 seconds between the first sighting of the iceberg and its collision with the Titanic, the officer fully relied on his past successes to make executive decisions in the present. We all know how that turned out.

Are You too Big to Fail?

History can be a great mentor.

The Titanic story is the most powerful example of a too-big-to-fail mindset. Sometimes the sheer size of a company creates an illusion of being untouchable and unsinkable. Enron, Lehman Brothers, Blockbuster, Toys-R-Us, Borders, Myspace, and Sears all went through the same process of blind belief in their own ability to withstand any storm or disruption.

The Titanic Syndrome has sunk many companies. It can be summarized as a corporate disease in which organizations that face disruption bring about their downfall through arrogance, excessive attachment to past success, or an inability to recognize and adapt to the new and emerging reality.

Slow Adoption is Gone

Start your new lifecycle now.

Once upon a time, our companies enjoyed long and healthy lives, with a slow rise to the top of financial performance and a gradual decline to annihilation. The rate of change was so slow that it was easy to develop the Titanic Syndrome and still survive — we had all the time in the world to renew a business on our terms. If a new “iceberg” showed up on the horizon — a competitor, a technology, a regulation — a company could adapt slowly and even enjoy the ride. But that fairy tale is long gone.

The increasing level of globalization showcased so painfully during the 2008–2009 global economic crisis and powered by the ever-increasing access to knowledge means that more of us are inventing every day and sharing those inventions globally. With all these pressures, the demand for corporate (economic, communal, and personal) reinvention has grown even further.

Does it mean that we are doomed? Absolutely not. What separates companies that survive from those that go down is the ability to start a new lifecycle, to pivot their company far enough from the path of destruction to find a new opportunity for growth. But if before you had 30+ years to reach your prime, today you might only have a few years.

How many exactly? To answer this question, we launched a global reinvention survey in 2018. Thousands of participants took part, giving much-needed insight into the speed of change and ways to deal with it. Our 2020 results showed that to survive today, 60 percent of us need to reinvent every 0 to 3 years, with a whopping 16.1 percent needing to reinvent every 12 months or less. This means that barely into a new business, you must start the reinvention process anew — again and again, in a continuous cycle of renewal.

The business you’re in today cannot be the business you’re in three years from now. By then, you’re either entering a new business model or you’re on the way to extinction. Period.